Climbing down from the family tree

and pulling it up by the roots, one fabulous read at a time

Before we begin

What are the strange and wonderful branches in your family tree or do you get more of a kick out of the gnarled roots and trunks that belong to other families?

Welcome! You’ve reached Spark. Learn more here or just read on. If you received this from a friend, please join us by subscribing. It’s free! All you have to do is press the button below. If you have already subscribed, welcome back! BTW, if this email looks truncated in your inbox, just click through now so you can read it all in one go.

Meet Rosalyn Tyo

This week, Rosalyn Tyo has graciously allowed me to reprint one of her posts from All By Our Shelves, the newsletter she was inspired to write when her husband died in 2018, making her a solo parent to two children. She was hungry for family stories that didn’t fall into the “traditional, idealized grouping of two adults plus kids.” I love family stories — the stranger and less traditional the better — and I love Rosalyn’s keen observations, honesty, and voice on the page. I am eager to share her writing with you and encourage you to check out All By Our Shelves whether you are looking for a new book or just want the feeling of sitting with a fellow traveler whose stories make you want more.

Rosalyn is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in Literary Hub, Scary Mommy, and elsewhere. She lives in Canada with her two children where she works with writers of novels and memoirs on their manuscripts as a beta reader and consultant.

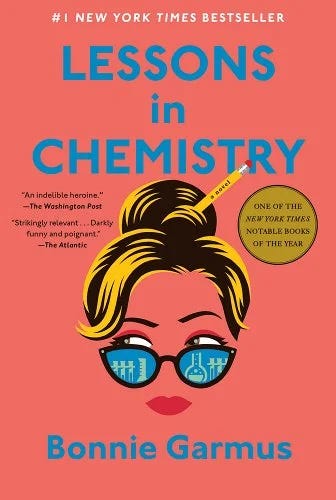

In this essay, Rosalyn takes a look at a book that I keep hearing a lot about but have not yet put on my TBR list, Lessons in Chemistry, whose protagonist has one of those family trees that widens eyes and takes a minute to explain. (I can relate as you can see in this old blog post. )

Now, onto Rosalyn, Lessons in Chemistry, and Remarkably Bright Creatures and whether or not a tree is the right metaphor for a family.

I’ll meet you in the comments along with Rosalyn!

Climbing down from the family tree

The family tree has been with us for centuries. It’s not the only way our ancestors came up with, when they found it necessary to formally delineate their biological relationships to each other, but it’s one of the most enduring and widely accepted. One reason for this, I think, is that a tree is so beautiful, to look at and think about—so much more inspiring than, say, a consanguinity table.

A tree is not only a flattering visual comparison for a human family, but an accessible one, in that most humans experience and appreciate trees, in one way or another, from a very young age. And as all parents and teachers already know, one of the easiest ways to introduce a brand-new, abstract concept to children, is to build upon their existing knowledge. You want to start with something concrete, that we can all see or feel and agree upon. If you’re my age or older, you probably drew a family tree in primary school, for these very reasons.

Even though a family tree doesn’t really make sense.

By that I mean, the metaphor does not hold up, because a tree just does not look or grow like a family. Even a little kid can see that a tree has both branches above ground and roots below, extending from a single trunk. To make this image work for a human family, you need to cut away some part of it, leaving either just the branches, or just the roots. And then you need to make a decision as to the orientation of what’s left. Do you ask the child to imagine themselves as the trunk, supported by the roots? Okay, sure, if you don’t mind answering a ton of questions as to whether they are above ground and the rest of their relatives are not…and you can breeze right past the fact that unlike the roots and trunk of a tree, a parent and child are not part of a single organism. If you don’t fancy that, you could ask them to imagine themselves as the lower-most branch of a tree that essentially has no trunk. So, more like a family shrub, that grows… downward only? Hmm.

Given such obvious issues, it’s hard to see why the family tree has persisted so long, as a metaphor. Unless, of course, you look at its roots.

Ever since the latter half of the eleventh century, Christiane Klapisch-Zuber writes, lineage has been “the fundamental structural mechanism of power and social reproduction.” Because wealth, prestige, and land were passed down along family lines, it was important to demonstrate one’s birth and membership in a “well-defined lineage” in order to get, or keep, your hands on these privileges. And, then as now, it made sense to represent lineage pictorially, because it is so cumbersome and difficult to convey in words alone. But why, of all things, a tree? Well, Klapisch-Zuber argues, perhaps the “vitalistic connotations” of a tree appealed “strongly to men who were anxious to ensure the future of their line and to root their dynastic hopes firmly in some mythic past.” By “vitalistic connotations” I believe she is implying, politely and academically, that this tree metaphor fit right in with some of his other botanical-and-misogynist ideas about sexual reproduction—you know, about planting his noble seed in the marital bed, and hoping that the soil was good enough to grow a male heir.

The family tree, and its gnarly roots as a mechanism for demonstrating genealogical superiority and preserving class privilege—has a central role in both of the “fabulous reads” I promised you, way back up in the subtitle: Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus, and Remarkably Bright Creatures, by Shelby Van Pelt.

In Lessons in Chemistry, it’s the early 1960s, and Madeline Zott has come home from kindergarten with a family tree assignment pinned to her sweater, which her mother is supposed to complete and return, along with a photo of her “whole family.” Madeline is vaguely aware that this assignment is going to be a problem because her parents, both brilliant chemists, were never married. Her father was an orphan, who never had a relationship with his biological family; both he and his adoptive parents died before Madeline was born. She has never met her maternal grandparents, either—one is in jail, the other is evading taxes in a tropical locale. To avoid raising the somewhat sensitive topic of her ancestry at home, Madeline heads to the library, in search of the information she needs in order to fill out the tree herself. When she and her classmates return their assignments, her nasty, snobbish teacher eats up the information “like a hungry virus” and shares it with “the other mothers, who spread it around like frosting.” The consequences of this invasive homework assignment prove to be far-reaching—both for Madeline’s biological family and her chosen one, the neighbors and friends who care for her—in ways that are both devastating and delightful.

In Remarkably Bright Creatures, both Cameron Cassmore and Tova Sullivan are obsessed with finding their next-of-kin. At seventy years old, Tova is the only living member of both her family of origin, as well as the small nuclear family she made in America, far from her native Sweden. She has good friends, but they are all of an age, and so she worries about who will take care of her, in her final days. She sits in the attic, sifting through her heirlooms, and thinking:

“All of these things had been stored away for her to pass along someday, relics to be carried up the branches of the family tree. But the family tree stopped growing long ago, its canopy thinned and frayed, not a single sap springing from the old rotting trunk. Some trees aren’t meant to sprout tender new branches, but to stand stoically on the forest floor, silently decaying.”

Cameron, on the other hand, was abandoned by his mother when he was a small boy, to be raised by his aunt. She did the job lovingly, if a little unconventionally, and he loves her for it…but envies his peers who, unlike him, got that head-start in life that comes of generational wealth, the college tuition fund or house down payment. Despite his natural intelligence, he blows his chance at higher education and drifts from job to job, all the while obsessing about what his parents owe him. He’s less interested in tracing his roots to the truth, and more interested in shaking that family tree, in hopes that dollars will fall down, like leaves.

However, as the Reverend Wakely explains to young Madeline, “families aren’t meant to fit on trees. Maybe because people aren’t part of the plant kingdom—we’re part of the animal kingdom.” Our kinship and equality with all living creatures lies at the heart of both novels, as both are narrated, in part, by an animal with an important role to play in the story: a giant Pacific octopus named Marcellus, in Remarkably Bright Creatures, and a stray mutt named Six-Thirty, in Lessons in Chemistry. I could go on for ages about both characters, and what they have to say about the nature of intelligent life, but I’ll save it, perhaps for another day.

For now, I’ll wind up by saying how hard it was to choose a direction for this essay, as these books have so many beautiful themes in common—I hope you’ll read them both, back to back, for this very reason.

Also, shameless plug time: I also wrote about Lessons in Chemistry, and some of my other, favorite themes (feminism! my remarkably bad attitude about cooking!) for LitHub, earlier this month. If you’ve got time, I hope you’ll read that, too.

And finally—one last word, on family trees. I just want to be clear that I don’t disapprove of geneaological research as a matter of curiosity, a way of learning about one’s heritage, and forming new relationships with blood relatives, both living and dead. My beef is with anyone who chooses to use their family tree specifically to establish their biological supremacy to someone else. As my daughters like to say, “that’s not a thing.” We all belong to the same big, dysfunctional family—humanity. - Rosalyn Tyo

Spark is Yours: Chime In

Hi there, this is Betsy again. Have you just finished a book you loved? Tell us about it. Got a great resource for readers or writers? Share away! How about sharing your book stack with us, that tower of tomes rising next to your bed or your bath or wherever you keep the books you intend to read – someday. And if you stumbled on a Moment of Zen, show us what moved you, made you laugh, or just created a sliver of light in an otherwise murky world.

Thank you and Welcome

Thank you to everyone who has shared Spark with a friend. Please keep it going! We are growing every week and it’s exciting.

Welcome to all new subscribers! Thank you so much for being here. If you would like to check out past issues, here’s a quick link to the archives. Be sure to check out our Resources for Readers and Writers too.

That’s it for this week. Let me know how you are and what you’re thinking about. And of course, always let me know what you’re reading. If there’s an idea, book, or question you’d like to see in an upcoming issue of Spark, let us know!

Remember, If you like what you see or it resonates with you, please share Spark with a friend and take a minute to click the heart ❤️ below - it helps more folks to find us!

Ciao for now!

Gratefully,

Betsy

P.S. And now, your moment of Zen…a golden arrival

This was taken last summer, on the day we arrived in Prince Edward Island, one of my favorite places on earth. The silhouettes on the shore are my daughters. It was their first time on the island, but not, I hope, their last. - Rosalynn Tyo

Calling for Your Contribution to A Moment of Zen

What is YOUR moment of Zen? Send me your photos, a video, a drawing, a song, a poem, or anything with a visual that moved you, thrilled you, calmed you. Or just cracked you up. This feature is wide open for your own personal interpretation.

Come on, go through your photos, your memories or just keep your eyes and ears to the ground and then share. Send your photos/links, etc. to me by replying to this email or simply by sending to: elizabethmarro@substack.com. The main guidelines are probably already obvious: don’t hurt anyone -- don’t send anything that violates the privacy of someone you love or even someone you hate, don’t send anything divisive, or aimed at disparaging others. Our Zen moments are to help us connect, to bond, to learn, to wonder, to share -- to escape the world for a little bit and return refreshed.

And remember, if you like what you see or it resonates with you, please share Spark with a friend and take a minute to click the heart ❤️ below - it helps more folks to find us!

What a feast this was to read. Thank you Rosalynne and Betsy!

Call me a sap but I love both equally. Some times I wish to stay with my roots especially when I find yet another part of the trunk I havent examined except some times its mulch adod about nothing so I just leaf it alone. But other times I like to branch out and pine fur the new and that is oakay too because it so elmentary and I feel all spruced up, you bircha

My double liking might not be poplar in some places but it's not mean or making an ash of myself, I just go aspen in the past because sometimes Im content with life and sometimes I sycamore because Im board and thats the plane truth but I dont want to palm off my views on anybody because that maple the wool over their eyes and make them feel bushed and that wood knot be good for anyone and ssome people might try to form a splinter group dust to be stubborn.