Before we begin…

Think about a time a book or a person confronted you with a truth that made you uncomfortable. How did you respond, by shutting the book or walking away? Did you find yourself grappling with new thoughts and old memories that wouldn’t let you alone? Did you ever feel moved to take action? I read one short essay and one book that stirred all this up for me. I’m still wondering what to do about it.

Welcome! You’ve reached Spark. Learn more here or just read on. If you received this from a friend, please join us by subscribing. It’s free! All you have to do is press the button below. If you have already subscribed, welcome back! BTW, If this email looks truncated in your inbox, just click through now so you can read it all in one go.

Why did these two writers get to me?

In the week since I last wrote, two stories entered my sphere that are prodding my brain the way my mother’s finger used to prod that spot between my shoulder blades decades ago. I am irritated, uncomfortable, but I can’t ignore what I’ve read.

The first was this brief piece by Elizabeth Aquino, “Maternal Wage Calculations,” the second was Deborah Copaken’s memoir Ladyparts. I was reminded all over again of the slippery financial slope where divorced women and single mothers struggle for footing, especially if those mothers are writers, especially if their children are disabled, especially if they are in middle age with bodies that are breaking down under the strain.

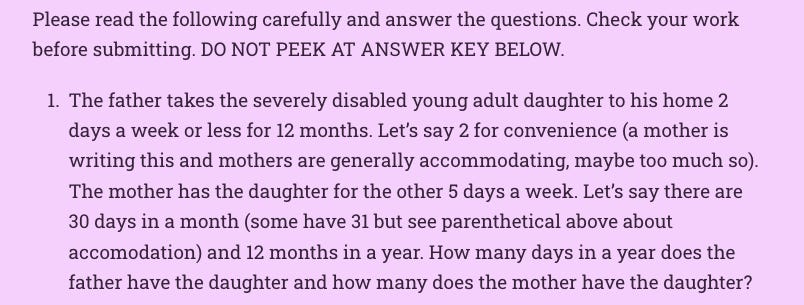

Aquino and Copaken are fearless, smart, witty, and furious. “Maternal Wage Calculations: Word Problems for the Weary” reads like those math problems we used to encounter in pop quizzes back in grade school. Instead of distance or speed, we are asked to calculate the breakdown of finances between two divorced adults responsible for an adult disabled daughter.

With each step in the problem and a few piercing asides, we discover the steep imbalance in hours and costs borne by each adult. The imbalance is steepened when one factors in the hidden costs and the not-so-hidden assumptions about the mother’s unpaid labor.

It’s a quick read but delivers a sharp sting. Aquino is not complaining, she is stating the reality of a situation that too many single parents, most of whom are women, are likely to relate to. Behind this reality is the larger one: that once a woman becomes a mother, she is more vulnerable to every inequity built into our laws, our business practices, and our ancient and entrenched cultural biases.

Should single parents be paid for the childcare part of their jobs? If so, how much? Who should be the ones who get to decide what is fair?

Debt, Blood, and A Lady’s Parts

The math worsens, of course, when women are in debt. In her memoir, Deborah Copaken struggles a lot with debt. Also with blood, lots of blood. The opening chapter, in particular, is not for the squeamish. It is meant to get our attention and to challenge us, dare us to look away.

Copaken has written a book about the years from her mid-40s to early 50s when her success as a writer fails to keep her and her family afloat in the face of shifting trends in the Internet and publishing industries. The result is a constant chase after the next paying gig, ideally one with health insurance, while also paying her children’s college tuitions, keeping up with constantly rising rent, separating from her husband, seeking love, paying off debt, acquiring new debt, or dodging the harassment from debt collectors and men who dangle employment in return for favors. Her body sustains one hit after another with emergency surgeries and new diagnoses that seem to unfold in sync with other life-changing events or lessons. She has organized the memoir in seven sections, each labeled with the body part that tried to kill her or at least slow her down: vagina, uterus, breast, heart, cervix, brain, lungs. A quick recap can be found in her bio on her website.

Some readers may find themselves overwhelmed by the torrent of disasters spliced with scenes, flashbacks, and factoids that start on the first page and don’t quit until the end. Copaken, who writes for The Atlantic and many other publications, has published six books: two novels, two memoirs, and two parenting books. I knew of none of them until my husband brought me Ladyparts from the library a couple of weeks ago thinking I might appreciate it. Now I realize that Deborah Copaken is everywhere and has made a living mining her life for stories. She is the kind of writer who, when being fired over Zoom from a corporate job with health benefits, makes mental notes even as she begins to hyperventilate because she will pitch a story about it to The Atlantic where she appears frequently. Nothing is wasted and if possible, material is leveraged for multiple stories. In fact, many of the essays that appeared elsewhere turn up in Ladyparts.

From the outside, Copaken’s story is that of a person whose life should have been smooth sailing. She was born to a lawyer and a homemaker in Maryland, graduated first from a private school and then from Harvard both of which she attended with financial aid. An award-winning war photographer, she was able to switch gears and become a working writer with a vast and glittery network of mentors and friends she mentions often (Nora Ephron, Meg Wolitzer, various Hollywood writers and producers). She has written for television (Emily in Paris, Modern Love) and her own memoirs have been optioned or are in development for the screen. Her husband of 20+ years was in tech. She has three smart, healthy, interesting children, one of whom was an actor as a child.

So it’s a surprise when we learn she has had to beg friends for money or resists calling an ambulance she can’t pay for even though she is bleeding out on her kitchen floor. It’s unsettling to learn that she must make large payments to a dishonest debt consolidator for years because she didn’t understand the fine print ,or that she ends up paying her husband’s credit card debt as well as her own because it’s years before she can afford the divorce process. She acknowledges the privileges she’s been afforded but provides example after example about how they have not protected her in a system that is rigged. And if it is rigged against women with her background, the implications for those who don't share it are obvious.

I cringed at times as I read this book. For one thing it is a kitchen sink of a memoir - so many incidents poured in that sometimes it was difficult to know where I was meant to focus. I was also tempted to criticize Copaken’s choices, something that others - including women – have done to her face and in their own writing. Her response to this criticism shamed me, and got me to finish the book. What is behind that desire to judge her, to resent the attention she is seeking for herself and for the larger issues she is writing about? She nails it when she says:

“One of the dirty little secrets of human nature is that, while on the surface most of us are charitable or at least consider ourselves to be, subconsciously we judge or in some cases abhor misfortune’s victims. This is a form of psychic protection against the very real possibility of our downward spiral. Blame the person falling off the ladder, not the system that sent them plunging.” - Deborah Copaken, Ladyparts

In other words, if it can happen to her, it can happen to me and I don’t like to think about that. There is a difference, though, between accepting the consequences of one’s own questionable decisions or actions, and accepting the consequences of an illness or job loss that is outside of one’s control and made worse by society’s refusal to figure out an equitable approach to health care, support for families, or any of the others policies that would keep more if not all families afloat when they are facing setbacks.

Can I relate? Let’s see.

When I started my dream job right out of college in 1978, I took home $110 a week after taxes. My rent was $250 a month excluding utilities. Babysitting and daycare for my three-year-old son averaged another $200 a month. Even when my supportive boss rushed through my raise a few months after I started, my take home pay was only $135 a week. I did not qualify for food stamps because I owned a car. I was on the hook for food, utilities, gas, car maintenance - in other words, I ran my life at a deficit from the get-go which was only possible because I had no college debt thanks to the foresight of my grandfather and parents, my mother gave me her car, and she, my dad and my stepfather sent cash at regular intervals. They did this because they loved me and because they believed, as I did, that this job would be a launchpad to independence. In fact, that was the thinking behind every hire the paper made, my boss explained. The paper had a track record of sending its reporters off to major national newspapers or to successful careers in editing or other careers in journalism. The publishers used this, in part, to justify their low-cost labor approach. This was a place where we were to pay our dues, improve our skills, and leave.

This was great for the publisher and okay for my single coworkers, but really challenging for me, a newly-divorced single mother in her early twenties. Still, I knew how lucky I was. I had generous relatives who believed in me, a job I loved, a boss who worked hard to make up for the lack of money – he and his wife became lifelong friends and even babysat when I had night meetings. I met a dear friend who became my son’s godmother when she joined the paper as an intern and needed a place to live.

Then I fell in love and moved to another state without a job or support network, an error in judgment that I paid for with sinking self-esteem, spotty employment, and worsening debt. I spent most of my time and energy trying to hide and juggle creditors, racing to keep enough money in the bank to cover checks, seeking shame-inducing bailouts from family, and shrinking from humiliating fights with my so-called partner. He kept a roof over my head but also created a confusing, constantly shifting set of expectations about what being a couple meant in both emotional and financial support for each other. We let each other down often on both fronts. Because I was an embarrassment to him, though, he used his connections to help me find contract work and encouraged me to go to business school (I took out the loans, he kept that roof over my head) and eventually I could leave what had become a toxic situation for me and my son, and, even more importantly pay all my own bills including my student debt. I was no longer a journalist or a writer. I worked for consulting firms and a pharmaceutical company.

That’s the condensed and somewhat sanitized version of more than a decade that taught me some hard lessons:

Don’t let Cobra lapse because that is when your child will have to be hospitalized for ten days and then require months of home care

Don’t move anywhere for love - get a job first.

In all job interviews make it clear (even though you KNOW it’s illegal for the interviewers to ask) that a) your child will not impede your ability to to your job, and b) your biological clock went off prematurely and no further pregnancies will be happening on their time.

Do not say anything when these same employers hire a man your age, with exactly your experience, at $5,000 more a year than you.

Oh, and don’t tell the corporate executive who’d hired you to do a few months of writing that could turn into a full-time job why you showed up on your first day of work with a black eye that could not be hidden with makeup or glasses. Understand that the look on his face when he sees it means that black eye has shaped his view of you in ways you will not be able to change, never mind how it has cemented your view of yourself.

I have been fortunate. All along I have had a safety net woven of love, family, friends, and luck. As I closed the pages of Ladyparts with the taste of survivor’s guilt in my mouth, all I could think about were the single mothers who do not have any safety net at all and never did. They don’t deserve my judgment, they don’t care about my survivor’s guilt. They do deserve my attention.

“They say money doesn’t buy happiness. That depends on how you define happiness. It sure does buy time, convenience, childcare, breast scans, and professional opportunity, all of which can lead to greater happiness. So I’d like to amend that saying, if I may: An excess of money doesn’t buy happiness, but having enough money does, and not having any money whatsoever buys nothing but fear, anxiety, and life-threatening heart palpitations.” - Deborah Copaken, Ladyparts

ICYMI

Here is last week’s post, another thought-provoking piece of nonfiction by a writer I’ve always admired, Amy Bloom:

Welcome New Subscribers!

Welcome to each and every new person who has joined us in the past week. If you would like to check out past issues, here’s a quick link to the archives. Be sure to check out our Resources for Readers and Writers too. And help us spread the word by sharing Spark with your friends. Here’s a button to make that easy:

That’s it for this week. Next week, I plan to ask for your input on some upcoming issues. In the meantime, write to me or comment below. Let me know you are and what you’re reading. If there’s an idea, book, or question you’d like to see in an upcoming issue of Spark, let us know! Use the comment button below or just hit reply to this email and send your message directly.

And remember, If you like what you see or it resonates with you, please share Spark with a friend and take a minute to click the heart ❤️ below - it helps more folks to find us!

Ciao for now.

Gratefully,

Betsy

P.S. And now…your moment of Zen: A Chicago Sunset

Jolene Handy of Time Travel Kitchen snapped this photo from the shores of Lake Michigan. I call this cloud therapy. I can’t be tense when I look at this sky, this beauty.

Calling for Your Contribution to “Moment of Zen”

What is YOUR moment of Zen? Send me your photos, a video, a drawing, a song, a poem, or anything with a visual that moved you, thrilled you, calmed you. Or just cracked you up. This feature is wide open for your own personal interpretation.

Come on, go through your photos, your memories or just keep your eyes and ears to the ground and then share. Send your photos/links, etc. to me by replying to this email or simply by sending to: elizabethmarro@substack.com. The main guidelines are probably already obvious: don’t hurt anyone -- don’t send anything that violates the privacy of someone you love or even someone you hate, don’t send anything divisive, or aimed at disparaging others. Our Zen moments are to help us connect, to bond, to learn, to wonder, to share -- to escape the world for a little bit and return refreshed.

We need to elect more women to public offices, state and federal. Our laws providing safety nets for families and low income people are pathetically inadequate. This can change (see European countries) but only if we women vote.

Ugh so depressing. I feel this as a single mom with an autistic teenager. And I’ve got no one else. The dad is a dead beat dad now. 😢 So I write for my sanity, not for money, because it can’t pay enough.