Journeys with emperors

Gerald Kooyman and Jim Mastro on living and working at the bottom of the world

Listen now or catch the highlights below

Before we begin…

The people who live and work in Antarctica are not like most of us. What draws them? What helps some do better than others in an environment so punishing yet beautiful? If you could sit down and ask someone what it was like to be there, what would you ask? Add your questions in the comments because, this week, we have an expert who will answer them for you. Go ahead, ask — you’ll be enriching us all! ICYMI, I wrote about why this part of the world has a grip on me in last week’s Spark.

Welcome! You’ve reached Spark. Learn more here or just read on. If you received this from a friend, please join us by subscribing. It’s free! All you have to do is press the button below. If you have already subscribed, welcome back! If you see something you like, please hit that heart so others can find us more easily. And if this email is truncated in your inbox, just click the headline above to come on through and read everything all at once.

The beginning of a long, cold, magical relationship

It was an Antarctic meet-cute story. Back in 1961, Gerald Kooyman (Jerry) was just a grad student sitting on the ice, taking a break from assisting with a study of cold-water fish, when a few feet away, a huge black form surged through the thin ice and tobogganed towards him on its belly as if Jerry were exactly the person he was waiting for. That’s when Kooyman came face to face with his first emperor penguin.

“Then three others came and they walked right over to me,” he recalls. “It really captivated me. I’ll never forget it.”

That one meeting led to thousands more as Kooyman traveled to one of the most remote places in Antarctica again and again over three decades to live among one of the largest emperor penguin colonies while they raised their chicks, hunted, dodged leopard seals and killer whales, and demonstrated the kind of extreme diving skills that humans can only dream of. He and his teams discovered that these birds can dive to depths of more than a third of a mile and cover distances of hundreds of miles. Their lives, in fact, are spent mostly at sea except for the periods when they hatch and fledge their chicks and, later, when they molt - lose all their feathers and grow new ones. It is then that the emperors are at their most vulnerable because without their feathers, they cannot swim which means they must fast because they cannot hunt for food beneath the water or they will die.

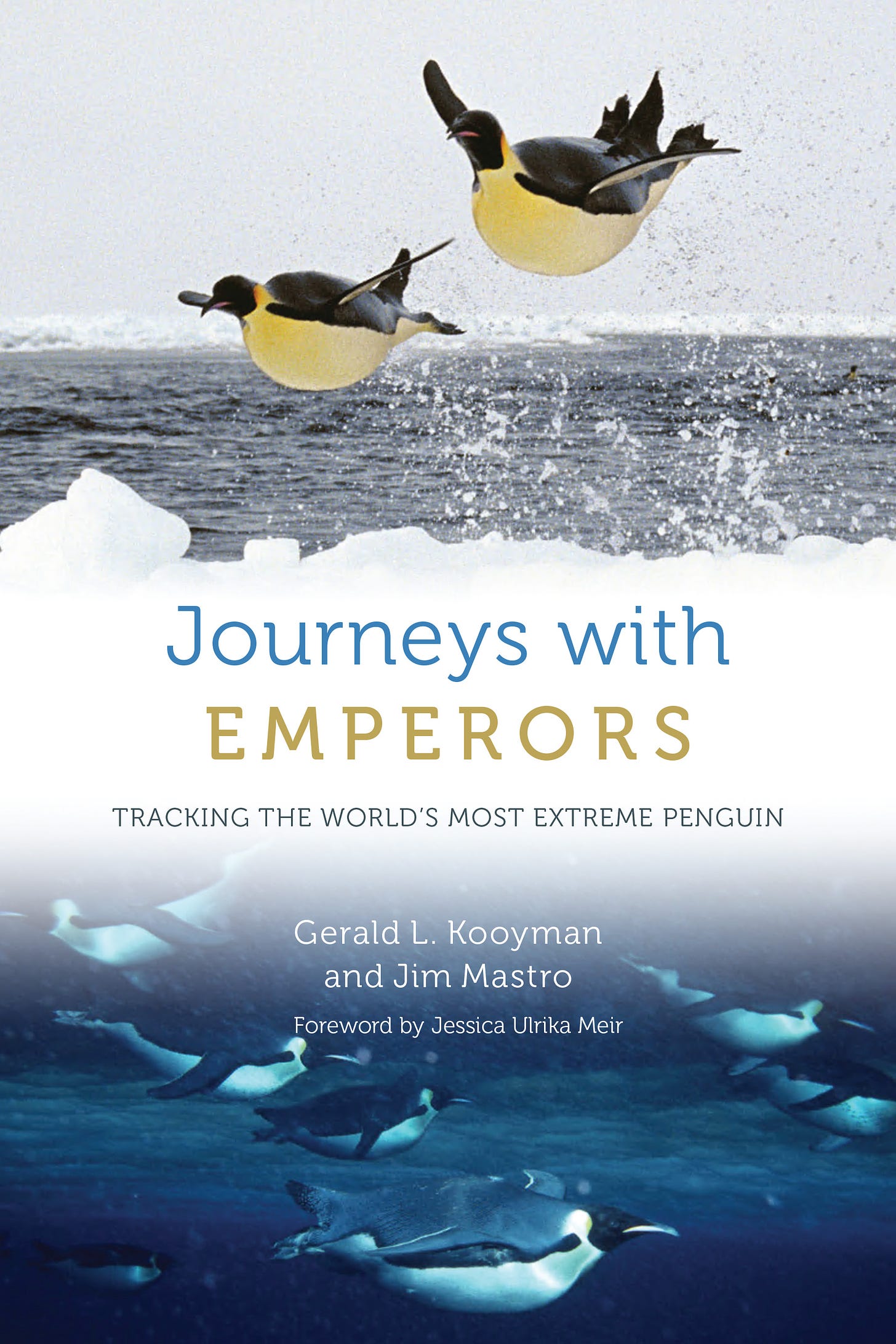

In his new book, Journeys With Emperors, Jerry Kooyman describes what it took to find Cape Washington, a remote area in the Ross Sea, and the arduous journey required to get to the colony of penguins there. He describes the sounds, smells, joys, and challenges of camping in tents with his teams for nearly three months at a time. He shares several never-forget moments with the birds and with their natural predators, the leopard seal and the killer whale. In short, it is a fascinating read with gorgeous pictures and lots to offer those of us who may never experience what it is like to live and work at the bottom of the world.

To write the book, Jerry worked with his colleague, friend, and one of our Spark authors, Jim Mastro who has spent 77 months in Antarctica and has lived through two winters at McMurdo station. I had the opportunity to speak with them both and am thrilled to share our conversation with you. You can listen by clicking the link above but before you do, check out Journeys With Emperors which launches on November 29 but is available for pre-order right now wherever you buy your books. If you know anyone with a fascination for extremes, nature, and all things Antarctic, this would make a terrific gift. It also provides plenty of motivation for preserving one of the world’s wildest places.

Special opportunity!

If you have questions about what it is like to live and work or just be in Antarctica, Jim Mastro has offered to take your questions. Just leave them in the comments (I’ll be sure to make sure he sees the ones you asked last week). He’ll be monitoring and will answer them there.

Highlights

Here are some highlights from our interview and nuggets from the book itself.

Getting to the penguins

The logistics of the first trips to Cape Washington were daunting. They first flew onto a glacier and then had to traverse with snowmobiles over or around crevasses, spending many nights with tons of equipment in small tents, before they could settle among the penguins. Later Jerry found a way for his team and him and all their supplies to be flown in on a Twin Otter aircraft. The descriptions raise all kinds of questions about motivation and the things that help a person succeed or fail on the ice.

What it takes to endure

“Cape Washington is a trying place..You want people who are really interested in the project, or interested in biology. You don't want somebody that's down there for the money and that it's a job and that's why you're going there. The job is secondary, third really.. You sort of talk with people that say they'd give their left arm to go with you…and people that are fairly calm, you know, don't get angry too easy.” - Jerry Kooyman

“If you're going to spend the winter, it has to be someone who's comfortable with being isolated not only from the world, but to undergo a bit of sensory deprivation. Because in the winter...it's dark all the time, so your visual sensory input is limited. Food becomes very monotonous, pretty much all you smell is diesel. It’s almost like being in an isolation tank in a way. So, you have to be comfortable with that kind of sensory deprivation. And also there's a bit of emotional deprivation, because if you see the same people... you don't get a lot of stimulation, that kind of emotional deprivation, I think, is something that hasn't really been talked about much. What is talked about is how small things in the winter can become big, small little issues can become really big issues, and there's a lot of emotion over things that there shouldn't be, and I think it's because when you undergo that kind of emotional deprivation even feeling angry feels really, really good because it's something to feel.” - Jim Mastro

How to hug a penguin

Tracking a penguin’s dives means placing a transmitter on them.

While it causes no discomfort to the birds, getting it on there was tricky in the beginning before simple innovations such as placing a hood over the head of the bird made it easier, according to Jerry. “An emperor runs from 60 to 80 pounds. And they're all muscle. They’re very gentle, mellow animals until you mess with them and then they get very difficult. Once you get close enough that you sort of give them a bird hug, they start whipping their wings and they're really strong.

We went through a phase where we got beat up pretty badly. One of the things we learned was to wear goggles because you want to protect your eyes. And the other thing is to wear a heavy parka, which you would be anyway because it's cold out there all the time but besides keeping you warm, there's a lot of padding. Everyone loses their enthusiasm for hugging an emperor penguin very quickly.” - Jerry Kooyman

The sounds of Antarctica

“When you're in a penguin colony, it's never quiet. Just skiing through it is one of the greatest experiences you can have, hearing all that noise and just slushing along. It's wonderful. It's like you're part of it.

The sounds of a penguin colony

Even though they were at least a mile away, we could hear leopard seals calling through the ice. It would transmit through the ice when we were in our sleeping bags and everything was quiet. They have a very haunting call and so we’d lie there and be lulled to sleep by the lullaby of Cape Washington. That's why camping was so valuable to me, is that we were right in it all the time.” - Jerry Kooyman

The lullaby of leopard seals

“One winter, a friend and I were walking back from Scott Base to McMurdo, and we paused at the top of the rise looking over the Ross Ice Shelf. There was no wind. It was winter, so it was nighttime. I think there was a partial moon, so there was a little bit of light. And it struck me, all this emptiness out there, not another human being except for McMurdo for thousands of miles, and not a sound, not a single sound. The only thing that I could hear was the blood rushing in my ears.” - Jim Mastro

The future for Antarctica and the emperors who live there

The partial collapse of the Thwaites glacier and the massive die-off among emperor chicks due to thinning and disappearing sea ice have been well-chronicled this year. While the perishing of thousands of chicks is a concern, Jerry says, the emperors can endure if adults are not threatened and can go on to reproduce again. If the sea ice is not sufficient for them during the period of the molt, or the food supply is not adequate to keep them alive while they fast, then future generations are at risk. Right now, there is not much information available about the status of the many adult penguins who travel far once they leave their chicks behind to make their own way.

“Where the birds molt, they need supportive sea ice. And right now they're not watching those (areas) because they don't know where they are to any degree. There are two things to be concerned about: One, ice breaking up too soon on them at a time when they can't (shouldn’t) get wet. And the other is that they need to really fatten before they go into that period of molting. It's another fast of 35 days, which isn't as long as a breeding fast, but it's more energetically demanding because they're producing feathers.” - Jerry Kooyman

The impact of spending many years “on the ice”

“I've seen a lot of primitive places that some of them are not so well looked after, but all things considered they're still in a wild stage that we don't have here anymore. And so we get a, we gain a greater sense of, of what we're, we've lost and what we're losing by some of the ways we use the environment or use the resources. And so that's, you, you come away, you can't, get that off your mind. And I don't think in terms of myself, I've, I've done my time of having wonderful experiences in the wild. My sons have to a great extent as well, but I think about my grandchildren.” - Jerry Kooyman

“It's a spectacular place. One thing that I always thought about when I was there was, you know, this is like the last place on this planet that we haven't spoiled. It's really our last chance to do things right. I think that that really made me much more aware of environmentalism and how it's important we take care of this planet. Over time I've become even more aware of that, because although people say, you know, we're destroying the planet, well, we can't destroy the planet. What we can do is destroy the planet's ability to support us as a species, and that we are doing, with alacrity. So I think I became much more aware of that, of our place on this planet. And our responsibility to the planet by being in Antarctica and seeing the wildlife in its purest form.” - Jim Mastro

A bit more about Jerry Kooyman and Jim Mastro

Gerald L. Kooyman is professor emeritus and a research physiologist in the Center for Marine Biotechnology and Biomedicine at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego. He has made about fifty trips to the Antarctic, and for the last three decades, his work has concentrated on studies of emperor penguins. He is coauthor of Penguins: The Animal Answer Guide.

Jim Mastro spent over six years in Antarctica (including two winters) as a laboratory manager, scientific diving coordinator, dive team leader, and research assistant. Most recently, he worked for several years as a technical editor in support of the US Antarctic Program. His coauthored book Under Antarctic Ice: The Photographs of Norbert Wu was named by Discover as one of the twenty best science books of 2004. He is also the author of A Year At The Bottom of the World, an account in words and photographs of his time wintering over in Antarctica. He lives in New Hampshire. You can find him on his website and follow him on Facebook.

If you like what you see or it resonates with you, please share Spark with a friend and take a minute to click the heart ❤️ below - it helps more folks to find us!

Penguin watch party

This presentation with photos and videos was given by Carsten Kooyman, Jerry’s son, who accompanied his father to Antarctica more than once.

Treat yourself to a few minutes above and below the ice with these short videos taken during the years Jerry Kooyman and his teams spent with the emperor penguins. Just click on the links to watch:

Adult emperors would also like to stay away from the teeth of leopard seals. In the water they out-swim and out-dive the predators. Here, they “fly” out of the water and get away from the holes as quick as they can.

Welcome New Subscribers!

If you’ve just subscribed, thank you so much for being here. If you would like to check out past issues, here’s a quick link to the archives. Be sure to check out our Resources for Readers and Writers too where you will find links for readers, book clubs, writers, and writing groups. And if you’d like to browse for your next read, don’t forget to check out books by authors in our community at the Spark Author Page which will be updated with new names and books for next week’s issue. Another great source: the many wonderful reviews you’ll find among the #Bookstackers.

Let me know how you are and what you’re reading. If there’s an idea, book, or question you’d like to see in an upcoming issue of Spark, let us know! Use the comment button below or just hit reply to this email and send your message directly.

And remember, If you like what you see or it resonates with you, please take a minute to click the heart ❤️ below - it helps more folks to find us!

Ciao for now!

Gratefully yours,

Betsy

P.S. And now, your moment of Zen…coexisting

Caption contest anyone?

Weddell seal, Madonna and child

Calling for Your Contribution to “Moment of Zen”:

What is YOUR moment of Zen? Send me your photos, a video, a drawing, a song, a poem, or anything with a visual that moved you, thrilled you, calmed you. Or just cracked you up. This feature is wide open for your own personal interpretation.

Come on, go through your photos, your memories or just keep your eyes and ears to the ground and then share. Send your photos/links, etc. to me by replying to this email or simply by sending to: elizabethmarro@substack.com. The main guidelines are probably already obvious: don’t hurt anyone -- don’t send anything that violates the privacy of someone you love or even someone you hate, don’t send anything divisive, or aimed at disparaging others. Our Zen moments are to help us connect, to bond, to learn, to wonder, to share -- to escape the world for a little bit and return refreshed.

I can’t wait to see what you send!

And remember, if you like what you see or it resonates with you, please share Spark with a friend and take a minute to click the heart ❤️ below - it helps more folks to find us!

Last week, from @Janice Badger Nelson: my husband and I watched documentaries about ships going there (to Antarctica). It looked so perilous however, especially Drake Passage. I would love to hear more from your interview about that passage. Looking forward to part 2. Jim: did you ever go by ship or were you always transported by plane? What insights can you share about the Drake Passage?

This question came last week From @Mary Hutto Fruchter (Writes Mary’s Pocketful of Prose) for Jim:

Is it true that you have to have your appendix removed before traveling to Antarctica? How does 6 months of darkness effect mental health? How do people cope?