Strangers in a strange land

Summer of 1974: a Pinto, my brother, a lot of rain, and the book that saved us

Before we begin…

I’ve found in the months since my brother’s death last February that the biggest gift someone can give a grieving person is to simply say, tell me about them.

Of course, you can’t tell everything, not in one go. But inevitably, a simple question like this brings an image or a moment or just something we love about them to the surface. A bit of joy for the teller and the listener.

We’ve all lost people, animals, places, or things we’ve loved. Please, share one thing about them now. Tell us the story or moment that surfaces for you.

Here is mine. The first part is a reprint of an old blog post I wrote several years back. The second can be viewed as a sequel. Both offer a small glimpse of my brother who would have turned 67 on July 10.

Thank you for the gift of letting me share.

Strangers in a strange land

Michael Valentine Smith may have prevented a murder back in the summer of 1974 when my brother and I were stranded in Port Angeles, Washington for nearly ten days. In a Pinto station wagon. In the rain.

It was day five or six. I remember the relentless drumming of water against the car roof. I remember waiting to take my shower in the campground's bathroom, hoping someone would leave her soap or shampoo behind because I was out. I remember, in a what-the-hell moment, that we spent our last few dollars in an expensive touristy restaurant where my brother and I inhaled giant roast beef sandwiches that came with crisp pickles, french fries, and one little plastic cup of horseradish. I confess to leaving the ramekin of horseradish untouched and waiting for my brother to do what I knew he would do: scoop up the cup of horseradish, ask "what's this?" then, without waiting for an answer, squeeze the entire contents of the cup into his mouth.

We knew each other well, my brother and I. We should have. He was less than a year younger than me and I have no childhood memories that don't include him. And, after three and a half weeks of traveling together in the 80-cubic-foot confines of my mother's green 1974 Pinto station wagon, we'd absorbed knowledge of each other the way our sleeping bags absorbed the water dripping in through the window. Since our -- okay, my -- second fender bender we had not been able to close it all the way. I knew he'd eat that horseradish because at that point there wasn't much we wouldn't eat.

After that meal, we were officially out of money. We had a few more days paid at the campground, a dozen packets of instant oatmeal, some tea, and a can of beans. That would be it until my mother could send a money order from the savings I'd left behind in New Hampshire. Our plan to pick up odd jobs failed when employers realized we were too young to serve liquor and not likely to stay through the summer into the fall. Besides, we smelled like wet socks left to rot in a gym bag for months.

It was in Port Angeles that two events occurred. We had a huge fight and we met Michael Valentine Smith. The argument cleared the air, metaphorically speaking anyway. Michael V. Smith guided us back to each other.

The argument, in hindsight, was long overdue. Friction began to erode our bravado our fist day on the road when I rammed the Pinto into a car in front of us on the Tappan Zee bridge. Other sources: our rapidly dwindling money supply, the question of whose idea this trip was anyway (mostly mine with an unexpected assist from our mother who urged me to take her car, and my brother), and the tyranny of AM radio which alternated between The Hues' Corporation's "Don't Rock the Boat," and Diamond Earring's, "Radar Love" until we were ready to gouge the radio out of the dashboard.

Just a couple of weeks earlier, he had turned 17 and I had turned 18. We’d planned to celebrate: I was old enough to buy 3.2 beer legally in Denver, a moment I had thought would stamp me as an adult. It didn't work. I was too shy to even walk into a liquor store and he couldn’t come with me because it would look like I was buying beer for him.

Our inherent shyness, acute self-consciousness, and naive lack of planning exposed us for the kids we were. The country had turned out to be so much bigger than I imagined; a thousand miles on a map was a matter of inches. Driving that same distance on the strange highways took us farther and farther from the familiar mountains of home thrilled me on the one hand and, on the other, dissolved my vague and romantic notions that all we would have to do is get going and adventure would find us. It might have if I’d been more willing to stop the car more often, walk around, and stop thinking about destination, timing, and what seemed “cool” versus stupid. My original idea was to hitch hike, maybe take buses along the way. It didn’t feel cool to have my younger brother with me. Worse, he’d never even wanted to come in the first place.

I was embarrassed by the time we reached Port Angeles. Nothing was more painful than confronting my own incompleteness and there was my brother, every morning, every afternoon, every night, a witness to my failures.

It added up to a combustible combination that seemed powerful enough that day to blow the doors off the Pinto. We fought. Insults were hurled. Doors were slammed. Blame was spread around liberally by both of us.

When we couldn't trust ourselves to say another word, we reached for our books. Books were our refuge, our allies, and a source of confidence since we'd been little because we'd both learned young, at four and five, during nightly lessons at my father's drafting table.

That night, after we finished yelling at each other, he grabbed his book and did his best to ignore my presence even though I was only a few inches away. After a while, the air stopped vibrating with tension and I remember being aware of the rain, the turn of pages, and my brother's breathing. Then he laughed out loud.

"What?" I asked him, seizing this as an olive branch, or at least a sign that the storm had passed.

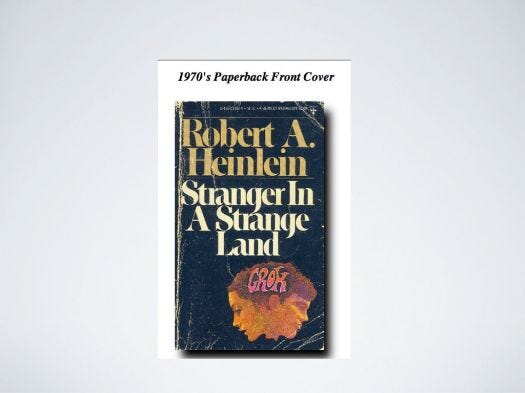

I don't remember the page he was on or what made him laugh but I saw that he was reading Stranger in a Strange Land, one of three Heinlein novels in a set he'd been given before we left. I'd already started it and wanted to keep going but it was, after all, his book. We started talking about the parts we had both read and then one of us, I don't remember who, started reading it out loud. We took turns and kept taking turns until we finished it.

“Love is that condition in which the happiness of another person is essential to your own.” ― Robert A. Heinlein, Stranger in a Strange Land

Here was a character who, like us, was thrown into the deep end of an experience without any understanding of the people, history, culture, or landscape. Without preconceived notions and no self-consciousness, this character's journey offered a few lessons about what it takes to really see, hear, and learn along with ideas about love, democracy, equality. I'm not sure how much we absorbed then though. It was enough to have found a way to talk with each other, to provide comfort and connection when we needed it most.

Very little evidence of our road trip remains. The Pinto is long gone. So are the photographs of the waves crashing off the cliffs of northern California, the giant Sequoias, Ben and Ricky Sue who picked us up on the two days we hitchhiked around Vancouver Island and showered us with hospitality in the form of beer and a guided tour, icy blue Kootenay Lake in British Columbia, and many, many campgrounds in the US and Canada. The copy of "Stranger" is gone along with the books that followed, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, and Time Enough for Love. Along the routes we took, we lost our fear of driving in cities and some of our shyness. We discovered that the world may be smaller than if feels sometimes when we found a car in Lake Louise bearing license plates from Coos County, New Hampshire. We learned that fender-benders don't define the success or failure of a journey and neither does running out of money in places like Port Angeles or, later, Medicine Hat, Alberta.

When I think of this trip now, I can see more clearly that when we left on our trip, my brother and I were strangers to ourselves and strangers to adulthood. We wanted to grow up, see life outside the White Mountains which had both shielded and imprisoned us. We were teenagers seesawing between seizing life and wanting life to leave us alone. When we came home, we had a lot of road left to travel but more confidence to do it.

Since then, though, we have never had that much time together and we have never read aloud to one another. If I could get one moment of that trip back, I think I would ask for a stretch of highway somewhere out of the rain. I would be driving to the sound of my brother's still-breaking teenage voice telling me the story of Michael Valentine Smith and taking comfort in being strangers together.

Sequel: connected by an author and his books

The sequel to the above story began some years after I was a mother, my brother Peter was a father, and we were both as far from getting into a car together for another long trip as we could be. I was living in New Jersey. He was living in New Hampshire. I’d visited a few more states by then. He’d visited or lived in all of them except for two. Then he went back to New Hampshire and settled in the place he would live and love until he died.

Way before then, however, he gave me another book, Where the River Flow North by Howard Frank Mosher. Even though Mosher wrote about northern Vermont, my brother told me the book reminded him of New Hampshire, of what it felt like when we moved there as kids, once again strangers in a strange place.

“sometimes, telling the story of a place is all you can do to preserve it.”

― Howard Frank Mosher, North Country: A Personal Journey Through the Borderland

The tough individuals in the book were characters we recognized even though Mosher had romanticized them. The land, the woods, the trees, the rivers followed across state lines from Maine, to New Hampshire, to Vermont. So did the place’s history.

We began a conversation, a kind of one-author book club, that spanned decades. Whenever one of us finished a Mosher book, we gave it to the other. We spoke regularly by phone and saw each other on visits but our discussions of the Mosher books were separate and special. We’d spend time conjecturing what really could have happened in the novel Disappearances , the story of a creative bootlegger/whisky distiller who knew every inch of Lake Memphremagog, with unforgettable characters, humor, and a slice of magical realism. We’d talk about the real people who seemed so similar to those in A Stranger in the Kingdom, right down to the name of the family that appears in so many of Mosher’s novels: Kinneson. That name seemed a stand-in for the surname Kenison, which connects generations of New Hampshire and Vermont families to this day.

Mosher was also a kind of stand-in for us. He was not a native of Irasburg, Vermont, the place where he taught and wrote for most of his adult life. He, too, had come from another place, in his case central New York. He fell in love with Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom the way my brother later fell in love with New Hampshire’s North Country.

If Peter and I read a Mosher story that left us wanting, it didn’t matter because it gave us something that was ours to talk about over when the paths of our individual lives threatened to take us away from each other. The day Mosher died, we called each other and had our own tribute. When the final collection of Mosher stories, Points North, was published posthumously, I bought it, read it, then immediately sent it to my brother as I had always done.

“Did you get it?” I asked him a little while later when I telephoned.

“Yeah,” Peter said.

“You read it?”

“Not yet. I’m not ready for it to be over,” he said.

Pete died in February of this year. We found the copy of Points North in his house among all the other things he left behind. I don’t know if he ever read it. I picked it up and tucked it in my suitcase. I wasn’t ready to read it again but I wanted the last book we’d shared. I wasn’t ready for our story to be over either.

I’m still not.

Watch: Where the Rivers Flow North

Ways to show you like what’s happening here

We don’t do paywalls here but we do work hard so if you’d like to show your support for Spark, click that heart so others can find us more easily. Share a post you liked with a friend or two. Spread the word!

And if you’d like to put your money to good work…

Consider a paid subscription ($5/month or $35/year) or use this as a link that will allow single contributions of any amount via PayPal.

There will be no paywalls. All subscribers will still have access to every post, archives, comments section, etc. If finances are an issue (and when are they not?), you can still show your support for Spark by participating in our conversations, “liking” a post by hitting that heart, and by sharing Spark among your friends. All of these things help bring new subscribers into the fold and every time we expand our audience, the conversation grows and deepens. Click below for more info.

Let me know how you are and what you’re reading. If there’s an idea, book, or question you’d like to see in an upcoming issue of Spark, let us know! Use the comment button below or just hit reply to this email and send your message directly.

And remember, If you like what you see or it resonates with you, please take a minute to click the heart ❤️ below - it helps more folks to find us!

Ciao for now!

Gratefully yours,

Betsy

P.S. And now, your moment of Zen…another summer long ago

Calling for Your Contribution to “Moment of Zen”:

What is YOUR moment of Zen? Send me your photos, a video, a drawing, a song, a poem, or anything with a visual that moved you, thrilled you, calmed you. Or just cracked you up. This feature is wide open for your own personal interpretation.

Come on, go through your photos, your memories or just keep your eyes and ears to the ground and then share. Send your photos/links, etc. to me by replying to this email or simply by sending to: elizabethmarro@substack.com. The main guidelines are probably already obvious: don’t hurt anyone -- don’t send anything that violates the privacy of someone you love or even someone you hate, don’t send anything divisive, or aimed at disparaging others. Our Zen moments are to help us connect, to bond, to learn, to wonder, to share -- to escape the world for a little bit and return refreshed.

I can’t wait to see what you send!

And remember, if you like what you see or it resonates with you, please share Spark with a friend and take a minute to click the heart ❤️ below - it helps more folks to find us!

My best friend Jimmy and I were both actors, so I asked him to join me at a Bastille Day brunch gig on Balboa Island playing (fully costumed) Marie Antoinette and Voltaire. I spent the day saying " let them eat cake" and he spent the day asking "What happens when you throw a bomb in the kitchen? Linoleum Blown-apart!" It was fun but not very lucrative after subtracting gas $ and the costume rentals but I treasure the memory, I especially recall our drive home and the endless laughter.

My mother kept encouraging me to make contact with my second cousin, Tony, & I kept dodging her constant, irritating encouragement. Tony was finishing up a musical theatre degree in Texas while I was working towards a degree (in anything) in San Diego. Mom kept saying, "you have something in common." I thought the commonality she was talking about was theater, not a lifestyle called gay.

Since I was going to spend the holidays with an old friend, Kathy, who I met in Germany when we were both involved the The Gallery Players (theatre group), I thought I'd ring up Tony and get my mother off my back. Well, we met and we became the BEST of friends. Finally I had an individual I could talk to...about anything and everything (theatre, boyfriends, sexual positions, et al).

We continued our relationship and I visited him in New York where he had gotten a few roles in Off Off Broadway shows, along with some leads in a few traveling shows. As far as I was concerned, he had made it in the Big Apple.

Our communication was less about books and more about theatre: plays and musicals. Tennessee Williams, Edward Albee, Eugene O'Neill, & Stephen Sondheim spoke to us; we loved to talk about these dramas & musicals and Tony would recite, or sing the lyrics for me.

Tony got AIDS and educated our extended families about this dreaded disease & we talked less about plays and musicals, and more about death. I remember visiting him for the last time in Bethlehem, PA; we wished one another joy and comfort & drama.

Every once in a while, when I listen to a musical or read a play, I can hear cousin Tony playing that part, and I smile.

Thanks, Mom, for pushing me into this short-lived friendship.