I hadn’t thought of Johnny Tremain for a long time and then, the other day, one of my favorite authors and unparalleled book evangelist David Abrams reported that he’d finally gotten a copy and was going to read it for the first time and I remembered.

“We give all we have, lives, property, safety, skill...we fight, we die, for a simple thing. Only that a man can stand up.”- “Johnny Tremain” by Esther Hoskins Forbes.

I read “Johnny Tremain” over and over again from about the time I was eleven to the time I was thirteen. It taught me that reading fiction could open the door to history and I read it so many times that my fingers turned green from the dye in the binding. Of course, if I hadn’t dropped it in the bathtub (the only place a kid from a large family can escape to be by herself), my fingers would go unstained and the binding would have lasted longer.

If you don’t know it, “Johnny Tremain” is the story of a stubborn, impatient, proud 14-year-old apprentice to a silversmith who injures his hand and must find another way to scrape together a living on the eve of the American Revolution. He ends up riding, first to deliver the patriotic newspaper The Boston Observer and then as a messenger for The Sons of Liberty. He meets everyone from Paul Revere to John Hancock along the way. He was my first introduction to a flawed hero who must overcome his own demons in order to be the man he is suddenly hungry to become. I think there was a time when I wanted to go back in time and marry Johnny and join him on the back of his horse.

But of course, he wouldn’t have let me. No one was fighting a war so a woman “could stand up.” The women in the novel were mothers, waitresses, the boss’s wife or daughter, and the quiet, strong young woman who loved Johnny’s hero, Rab. They would help from behind the scenes or, in rare real-life cases, on the battlefield, but would not reap the benefits envisioned by the writers of The Declaration of Independence.

Johnny’s militia wasn’t fighting for all men either. The majority of Black men and women remained slaves at the time of the Revolution. Native Americans are referred to in the very text of the “Declaration of Independence” as “savages” enlisted by the Crown to kill the colonialists.

“He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.” - The Declaration of Independence

As I read “Johnny Tremain” in the bathtub, swept away with the idea of fighting for something so grand and right as the American Revolution, I forgot that I was reading fiction. Many years later— an embarrassing number of years — I have come to understand that much of what I was taught about the “Declaration of Independence” and the American Revolution was not entirely true either because so much was left out. I have come to understand that the Revolution was about a certain kind of liberty for a certain class of white man. Poor Johnny couldn’t be expected to teach me all that, I suppose, but there it was, reflected on each the page of Esther Forbes’ book.

I had never considered what the celebration of July 4 might mean to a Black person, a Native American person or, later, to Chinese immigrants who built US railroads but were denied citizenship for so many years, or the Japanese immigrants and citizens whose property was lost when they were incarcerated during World War II even though they’d committed no crime.

Short Reads

Today’s reads provide a glimpse of what the celebration of our independence looks like through the lens of others throughout history.

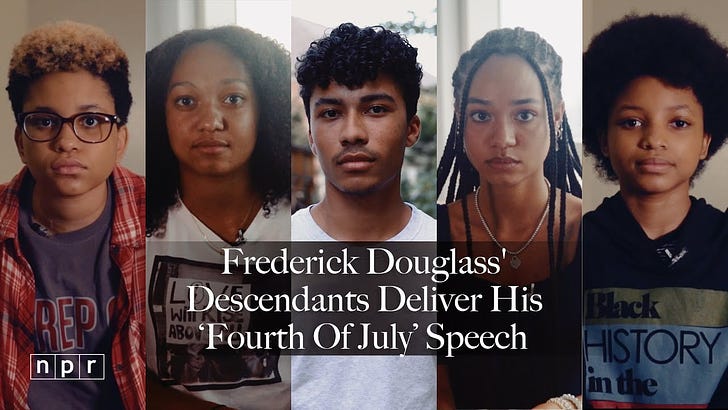

On July 5, 1952 Frederick Douglass was asked to speak at an event commemorating the signing of the Declaration of Independence in Rochester, New York. In it, he acknowledges his respect for the “fathers of this republic” as “great men…great enough to give frame to a great age” but also says, “the point from which I am compelled to view them is not, certainly, the most favorable.” Then he explains exactly why in searing terms:

“Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine…”

Here, Arielle Gray explains the tradition she shared with her grandfather each July 4 when they went to the Boston Common to hear Douglass’ speech read aloud and why the usual holiday celebrations don’t resonate with her:

“What, to us, is the Fourth of July when our freedoms are consistently infringed upon by a government meant to uphold those very freedoms? What, to us, is the Fourth of July when our freedoms are provisional and subject to alteration? What does the Fourth of July actually stand for? Does it mean something? Or is it an empty promise?”-As A Black American, I Don’t Celebrate the Fourth of July”

You can hear it read movingly by the young descendants of Douglass here:

Independence Day looked very different to Charles Kikuchi as he recalled observing it in an WWII internment camp with his family in the essay, A Doubly Strange and Bewildering Day: Views of July 4 from Behind Barbed Wire.

“…It is difficult to reconcile some things that have happened with true Democracy. Negroes are sent out to Australia to fight for Democracy; at home they don’t get a full share of it. Nisei boys serve faithfully in the army; their parents are sent to Tanforan.” —Charles Kikuchi,

And there is this commentary, The Dilemma of the Fourth of July, by Mark Charles originally written in 2015 about a moment when he is dining in a restaurant with other Native Americans beneath a copy of the Declaration:

“When our server, who was also native, came to the table, I asked if I could show him something. I then stood up and pointed out that 30 lines below the famous quote “All men are created equal” the Declaration of Independence refers to Natives as “merciless Indian savages. The irony was that the restaurant was filled with Native American customers and employees and there, in plain sight, a poster hanging on the wall was literally calling us all “savages.” - Mark Charles, The Dilemma of the Fourth of July

And this raises for me the questions of all the people being sworn in as citizens this week, the ones who have studied to achieve a command of facts I have long forgotten about our history and how our government works. They represent thousands of stories, hopes, dreams, and expectations. Will they find, for themselves or their children, what they are looking for after their years of work and study? I’m thinking of this story about hate crimes against Asian Americans in the wake of the Covid crisis and this TedX talk by Dalia Mogahed, “Freedom to Choose Faith-What it is like to be Muslim in America”

I’m not a historian. I’m not an academic. I can’t write with precision or authority about the mythology or reality of the American Dream or the economic and political factors that led to the Declaration of Independence. As a citizen and reader, though, I feel a dawning sense of responsibility to try to understand more than I have and to view this day and through the eyes of Americans who do not look like Johnny Tremain or me. I have to consider that whatever progress can be claimed about our country’s journey towards true freedom and independence for all of its people, we are not there yet. The good news? Johnny’s story ended on the last page of the novel. Our story continues. That is something we can celebrate.

A Longer Read

“It’s My Country Too” by Jerri Bell, Tracy Crow, with foreword by Kayla Williams. This anthology conveys the full spectrum of contributions and experiences of women in the U.S. Military, beginning with the Revolutionary War through the present day.

A Documentary

This five-part series Asian Americans produced by PBS was fascinating and showed examples of fine storytelling that kept me glued to the series until it was finished. It is a way to gain insight into parts of our history that we may have missed growing up. Watch for interviews later in the series by Viet Thanh Nguyen , author of the Pulitzer Prize winning-novel “The Sympathizer”, a book I could not put down until I finished it.

And Broadway on Disney: Hamilton

This musical about a man central to the formation of the U.S. we have today is on my agenda this weekend. To watch, you have to sign up for Disney Plus but it is only $6.99 for one month and then you can quit and since Broadway tickets cost more than a mortgage payment, this is a very cost-effective way to watch the original cast. Let me know if you’ll be watching this so we can talk about it.

I wish you a safe and healthy holiday weekend. Let me know how you are doing, what you are wondering about, and what you are reading. And if you’ve ever read “Johnny Tremain”, let me know what it meant to you when you read it or what it means now. It’s always really good to hear from you in the comments below or in my inbox. I am grateful for all of you.

And if you have a story — about what you read in the bathtub or someplace you went for privacy, a memory a time you first felt independent or most free, an encounter, a story of how you and your family spent this holiday under our new Covid-shaped conditions, or anything else that pops into your mind, share it with us. Use the comments below or respond to the email and I’ll share them, respecting your privacy of course.

I’ll add the books you’re reading or want to read to our list on Bookshop.org. If you’re prompted to add any of them to your collection, remember that every order from this list helps independent bookstores and can earn a little money over time that we can donate to literacy programs.

Stay well. Dive into a great read. Let’s talk.

Betsy

P.S. And now, your moment of Zen…A song that never fails to lift my heart and move my feet (when no one is looking). Here’s Donna Summer’s version of State of Independence.

And here’s the version with Chrissie Hynde and Mood Swings in case my sister’s reading. She knows which one she is and what this one brings back for us. And thank you.

I've currently got three going: Weather, by Jenny Offill (a novel in fragments; how does she do that?), How to be an Antiracist, by Ibram X. Kendi, and The Power of Ritual, by Casper Ter Kuile. Thanks for another excellent Spark-ing, Betsy.

I'm currently reading Memory Police by Yoko Ozawa and enjoying it a lot. I'm looking forward to Vernon Subutex 2 by Virginie Despentes (translated by Frank Wynne).