Late is better than never

My late-in-life relationship with poetry plus an interview with one of the poets among us: Andrew Merton

Before we begin…

Who is your favorite poet? And what is your favorite poem? How do you respond to poetry – do you, like me, sometimes struggle with poetry as an art form? What can poetry do that prose cannot? How has your relationship with poems as a reader or a writer evolved over the years?

Welcome! You’ve reached Spark. Learn more here or just read on. If you received this from a friend, please join us by subscribing. It’s free! All you have to do is press the button below. If you have already subscribed, welcome back! If you see something you like, please hit that heart so others can find us more easily. And if this email is truncated in your inbox, just click the headline, “Late is better than never” to this newsletter to come on through and read everything all at once.

I am not a poet

I have not tried to write a poem since eighth grade or maybe ninth. I was surprised by the early efforts that surfaced during one of those times my mother cleaned out her storage boxes full of keepsakes once taped to the refrigerator in our kitchen. I don’t remember writing them; there were only a few, undoubtedly inspired by a class assignment. They smacked of self-consciousness and teenage angst.

For years, I did not read poetry either. I would flip magazines open to whatever short stories I could find and bypass the blocks of verse cordoned off in the corners. When a novel like any of J.R. Tolkien’s series moved from prose to long chants and songs, I sped past them. Poems required me to stop, slow down, absorb or struggle to absorb sometimes opaque ideas or references, when all I wanted was to plunge forward.

I wonder sometimes how I came to love the written word so much and not to love poetry. It comes down in part to exposure. The adults who influenced my reading most growing up loved mysteries, novels, short stories, the news of the day. I know my teachers introduced me to poetry along with its various structures and forms. The only poet I remember from these years is Robert Frost whose poem “Birches” showed my friend Deb and me the very woods and ice storms that surrounded us where we lived. We were captivated by the idea of swinging birches – climbing to the top, leaning over, and waiting for it to fling us up again. One day the bus dropped us off at the end of our road and on the way to my house we dropped our bags and gave it a go. Either the trees were too small or we were too big. We failed but had a few laughs, laughs we still share to this day remember it. As I recall this, I’m thinking that the poem must have worked its way into us somehow. At twelve, we did not fully grasp what it meant to be “weary of considerations” and we understood only vaguely that life would be more and more difficult, but we sensed the resourcefulness and joy of a boy climbing a tree and swinging down to earth and back. We wanted to taste that for ourselves.

Has something you’ve read ever inspired you to try something you’d never tried before? How did it go?

Over the past few years, terribly late in my life, I’ve begun to read poetry. There are times when I feel shy and awkward about the whole thing but, mostly, I’m kicking myself for putting walls between myself and an art form that can condense worlds into a few lines. I find myself smiling or crying or just sitting in wonder as a writer shows me something new in the familiar. I notice I lean heavily towards poets who work with nature, including and perhaps especially, human nature. I like a good laugh, too. Who doesn’t?

I’ve leaned heavily on poets like Ted Kooser, Dana Gioia and Mary Oliver to pave the way for me. My heart and mind were blown open when Stacy Dyson, founder of Tesoro Women, performed her poetry live. These days, I read or listen to poetry with a kind of freedom that is missing when I read a story or a novel. I do not want to pick it apart to see how the author “did that.” I know and care nothing about structure or form. I can just let it in and see what works on me and what doesn’t, what makes me want to read or hear it again and again.

A Poet Explains: Interview with Andrew Merton

Among those who have led me back into the world of poetry as an adult, is the person who taught and mentored me as a journalist. Until he published his first volume of poetry, I did not know that Andrew Merton wrote poems. I learned only recently that he’d been writing them for twenty five years before he published his first of four volumes, the most recent of which, Killer Poems, was just released. He recently took a little time to answer some questions I had for him about the poems in this book and a bit about the journey that got him there. Read on to get his insights. Then, treat yourself to your own private reading by clicking the links throughout that will let you listen to Andy read from his latest book. You can find all of his books at bookshop.org or wherever you buy your books.

Here’s Andrew Merton:

“Ever since I was a kid, I have lived in a rich fantasy world. Ghosts, gremlins, werewolves, wizards, wampuses, hobbits (my mother read me The Hobbit when I was six years old)—and while I had an almost 50-year career writing nonfiction, I have never entirely left that world. Writing poetry brings out that aspect of me. Yes, it’s hard, sometimes frustrating work, but when I nail one, it’s sheer joy.” - Andrew Merton

Whe And here are his books:

Our conversation

You’ve mentioned in the past that you turned to writing poetry seriously in your sixties after years of writing and teaching journalism. Tell us more about your journey as a writer and your turn towards this art form. What role did poetry play in your professional or personal life before that? What drew/draws you to poetry, both reading it and writing it?

AM: That’s not quite right. My first book was accepted for publication in 2011, when I was 67, but I had been writing poetry for about 25 years before that. It is true that I had no interest in poetry in high school, or in college, where I trained to be a journalist. After five years on daily newspapers, in 1972, I was hired by The University of New Hampshire (UNH) to teach journalism. The UNH journalism program is in the English Department, so by a wonderful accident, I became friends with two fabulous poet-colleagues, Charles Simic and Mekeel McBride. In the fall of 1985 Mekeel invited me to take part in her graduate level poetry writing workshop; that’s when my poetry neurons kicked in. Mekeel assigned a lot of published poets. One of the first was Raymond Carver. Better known for his succinct short stories, Carver’s poems are like his stories, distilled to another level, like brandy to wine. He wrote short, declarative sentences. (Just like journalists!) There was nothing obscure about his stuff—and yet, somehow, there were always layers of meaning. I thought, Huh! I can do this! Carver was definitely my first role model (but far from my only one.)

The following semester, I took Charlie’s graduate workshop. As you know, Charlie, along with Mark Strand and very few others, was among the best surrealist poets in the world. That gave me a whole other dimension, which is why my own poems range from straightforward narrative storytelling, through some more figurative stuff with the occasional extended metaphor thrown in, on to surrealism. The one constant, I would say, is humor. While not all of my poems are humorous—a few are very sad—I have always relied on humor to leaven even some of the more somber stuff.

Listen: 50th Reunion, Class of ‘67 by Andrew Merton

Charlie and Mekeel changed my life. They introduced me to, and shepherded me into, a rich and wonderful world that I had been only dimly aware of, if at all.

Somewhere along the way I realized that, as a kid, I had loved some poetry, especially Dr. Seuss and Shel Silverstein. In 1991, when Dr. Seuss died, I wrote a tribute poem to him, “Of Moose and Seuss,” which was published in the Boston Globe and later in Lost and Found. Also my mother, who graduated from Barnard at 19, loved poetry; she would go around the house quoting Shakespeare (“Out, out, damned Spot,” when taking the dog out…) So it was there, latent, for the first 41 years of my life.

In 1986 I started sending some poems to journals, but it was very much on the side—I was still writing magazine articles and a weekly column for the NH Sunday section of the Globe, as well as teaching. It wasn’t until 1996, after the Globe column ended, that I started devoting the majority of my writing time to poetry, with some success placing some poems in journals. But it was not until 2010 that I felt I had enough good poems to do a book, and enough courage to look for a publisher.

On May 12, 2011, I was in my office at UNH when Katerina Stoykova of Accents Publishing called to tell me she had accepted Evidence that We Are Descended from Chairs. I closed my door and danced around for awhile…it was my birthday! Flat out best birthday present I ever had. Katerina, too, changed my life; it was not until the publication of that first book that I felt justified in calling myself a poet.

If you look over the poems in each of your four collections, what do you notice about your own work? Are there poems you included in Killer Poems that you couldn’t have written earlier? Why do you think that is so?

AM: Frankly I’m not sure much has changed. Each book contains a mix of narrative poetry, more figurative stuff, some surrealism. Each has a chronological spine. Each ends with a note of finality. I will say that after the first book I loosened up a bit—I wouldn’t have dared throw the Seuss poem or the off-the-wall “The Chicken Conundrum” (in Final Exam) into Chairs. Beyond that, I think an outside reader would be in a better position to discern any particular progression, or differences among the books.

If you were a visual artist, I would view your poems as sketches - the kind that are inspired by a glimpse of detail that illuminates an entire scene, shows the familiar in a startlingly new light. Sometimes this is quietly devastating. I’m thinking here of your poem, “Habit.” In the space of a few lines — just a scene of a man looking through a store window — you evoke an instantly recognizable gesture that, for me, echoed with denial. “Post ECT Briefing” puts us on a stretcher with a patient undergoing electroshock therapy who, incredibly, makes a pun at the end. What subjects or details tends to draw your attention and what doesn’t? Has this changed at all for you since you began writing poetry? And while we are on the subject of details, how do you capture the ones that strike you and bring them home to incorporate them into a poem? Do you walk around with a reporter’s notepad in your pocket?

AM: Regarding subject matter, while I do delve occasionally into serious family and life matters, I am mostly drawn to weird, offbeat, out-of-the-way stuff. For an extreme example, see Surrealism 101 Midterm Exam.) My work is populated with animals—probably the ones that show up most are quirky platypuses and walruses. (Lewis Carroll is an influence: The time has come, the walrus said, to speak of many things.) I am an avid New York Yankees fan (not weird, although, in New Hampshire, dark) but as a kid, while I admired the perfectly chiseled, handsome Mickey Mantle, I was much more drawn to the weird, lumpy, very funny Yogi Berra (with whom, I’m proud to say, I share a birthday.) Regarding inspiration, I mostly have to work for it. (Two exceptions: the deserted storefront in “Habit”—I mean, there it was—and the pileated woodpecker in “In the Woods,” who simply stared me in the face (Hey stupid! If I’m not a poem, what is?) Mostly, when I want to write a poem—or when I have to, on deadline for my writers’ group—I’ll surround myself with five or six books of poems that are inspiring me at the time, and flip through them until I find an image, a line, a stanza, even a title, that triggers something in me. I flat-out stole the title from “Review of an Unwritten Poem,” by an idol of mine, the late Polish Nobel laureate Wislawa Szymborska; while the titles are the same, the two poems are otherwise entirely different from one another. Anyway, once I have a trigger I free-write fast in longhand; once I have the gist of something, I switch to a keyboard. Speaking of deadlines, I thrive when I’m up against a tight one, be it in journalism or poetry. There’s usually an adrenaline rush.

Listen: Habit by Andrew Merton

In his foreword to your first collection, Evidence We Are Descended From Chairs? , the late Charles Simic wrote “Almost every one of his poems has a surprise waiting for the reader, either some astonishing figure of speech or a witty observation we are not likely to forget soon.” Are you ever surprised by what emerges as you work on a poem? Can you give an example?

AM: I am often surprised. Take “A Pious Man Explains Why He Quit His Job.” Most of it is a true story, told to me by a guy I knew years ago. But the last line just came to me— “Same with plastic Elvis”—and that put the needed twist on the poem. And I was more than halfway through “Ahead of His Time,” about Walt Whitman, not really knowing where I was going, when the last line came to me—“one line short of a sonnet”—and so of course I had to revise the thing to make sure it was thirteen lines.

You’ve mentioned that Charles Simic and Mekeel McBride were instrumental in your development as a poet. How do you think your work reflects their input or example over the years? What skills have you leaned on or developed further in order to write your poems?

AM: Mekeel McBride and Charles Simic were my seminal inspirations. Then there is my writing group of over twenty years. While the membership has changed over time—except for Mekeel, who has been in it from the start—it has always comprised skilled, publishing, extraordinarily generous poets. From them I have learned an awful lot about poetry. More importantly, I have learned to be humble, to be eager for any bit of constructive criticism, even if it is as blunt as “That just doesn’t work.” These people are family to me. Incidentally, for much of the time I have been the only man in the group. To me that is an honor.

What has no one asked you about you and your poetry that you wish they would? Feel free to ask and answer here!

AM: No one has asked if there is a side of me that poetry, in particular, brings out. To that I would say: ever since I was a kid, I have lived in a rich fantasy world. Ghosts, gremlins, werewolves, wizards, wampuses, hobbits (my mother read me The Hobbit when I was six years old)—and while I had an almost 50-year career writing nonfiction, I have never entirely left that world. Writing poetry brings out that aspect of me. Yes, it’s hard, sometimes frustrating work, but when I nail one, it’s sheer joy.

Listen: The Second-to-Last Unicorn Speaks by Andrew Merton

Finally, you once shared with me a very practical way for a non-poet, lay sort of reader who is a little self-conscious when it comes to reading and discussing poetry. I lacked full confidence in my ability to grasp and appreciate the art of it — my comfort zone is straight prose. I remember appreciating the very accessible, practical insight you provided. Will you share it again? I lost it in the great email deletion.

AM: Here is a handout I used when teaching poetry workshops. To that I will add:

Do not be intimidated by poetry. Some are more difficult to understand than others—some of it, frankly, seems purposely obscure; if you have a lot of trouble getting it, it’s not your fault. Read something else. There’s plenty of poetry that is either immediately accessible or accessible with a little patience. Reading it should never be drudgery. It might take a little effort, but it should be enjoyable.

Modern poetry runs along a spectrum from narrative story—telling (see: Robert Frost, Raymond Carver} to surreal (Simic, Mark Strand) with more figurative and symbolic poetry in between. Read a lot of it. Don’t try to figure out a deeper meaning for any of it, as you may have been taught to do (and been turned off by) in high school. When you come to a poem that’s abstract, don’t try to figure out what it means. Rather, view it as you would view an abstract painting. See if you can absorb it on its own level. In addition to the poets I have mentioned above, I have learned from reading many and varied fine role models over the years. Some favorites: Sharon Olds, Anne Carson, Jane Kenyon, Marie Howe, Billy Collins, Mark Doty, Louise Gluck, Natasha Trethewey, Joy Harjo…the list goes on.

More poets from the Spark community

What readers say: “Your poetry is like thunder and lightning and all that it's like to be a woman. Thank you for sharing your soul in words” --Mytrae Meliana, author of Brown Skin Girl.

Books: (Fiction) The Hounding, Till Darkness Comes, (Poetry) Desire Returns for a Visit, Poetry for the People, I Eat My Words

What readers say: "I Eat My Words, is a groundbreaking hybrid collection, executed with creativity, skill, and humor. In this romp through the worlds of poetry and mouth-watering recipes, the author has created a book that is practical, pleasing to the poetic sensibility, and downright fun to read."

Books: Forces; Permanent Change of Station; Uniform

What readers say: “There is so much life in these poems—daily life, and overarching life. As with Sylvia Plath, Louis MacNeice, Natasha Trethewey and others, Stice brings visions of war and peace, violence and tenderness, into the sort of troublesome, necessary contact we should always keep them in.” - Andria Williams, author of The Longest Night, A Novel

Let’s talk some more

What are you reading ( by ear or on the printed page) ? What do you want to read? Share a book rec, a poem, or just let us know what you’re thinking about here in the comments or other meeting places such as Notes here on Substack or the new Threads offering over on Instagram, or IG itself. You can find me on either of those social media sites under the handle of @egmarro_spark.

If you like what you see or it resonates with you, please take a minute to click the heart ❤️ below - it helps more folks to find us!

Thank you and Welcome!

Thank you to everyone who has shared Spark with a friend. Please keep sharing. Invite a friend to join us! Just use the button below.

And to those who have just subscribed, thank you so much for being here. If you would like to check out past issues, here’s a quick link to the archives. Be sure to check out our Resources for Readers and Writers too where you will find links for readers, book clubs, writers, and writing groups. And if you’d like to browse for your next read, don’t forget to check out books by authors in our community at the Spark Author Page which will be updated with new names and books very soon. Another great source: the many wonderful reviews you’ll find among the #Bookstackers.

Let me know how you are and what you’re reading. If there’s an idea, book, or question you’d like to see in an upcoming issue of Spark, let us know! Use the comment button below or just hit reply to this email and send your message directly.

And remember, If you like what you see or it resonates with you, please take a minute to click the heart ❤️ below - it helps more folks to find us!

Ciao for now!

Gratefully yours,

Betsy

P.S. And now, your moment of Zen…forgotten things and what they say to us

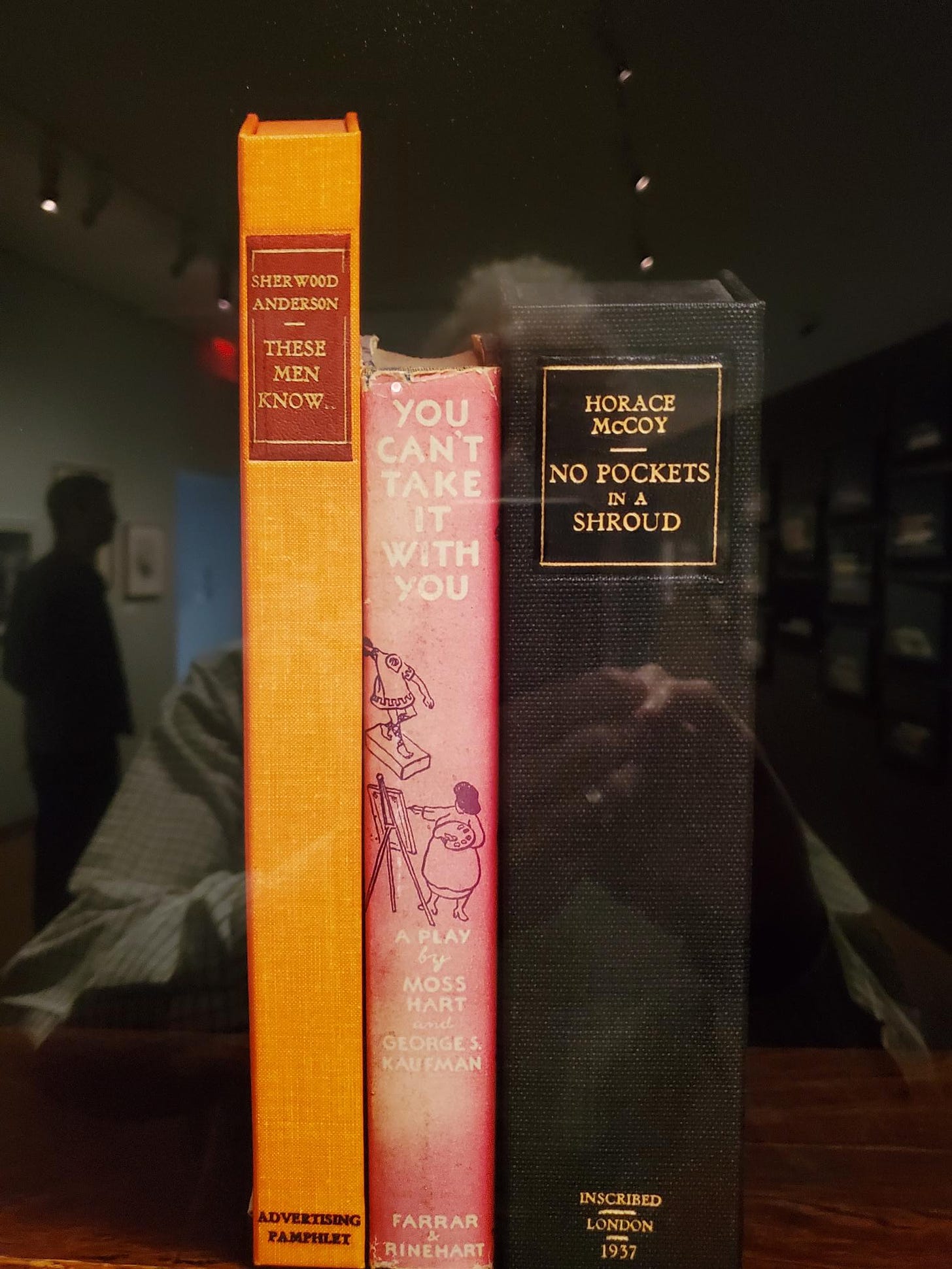

There’s the spine poem (poems created using the titles of books) and there is a whole spine conversation as Andrew Merton discovered when he and his wife checked out the J.P. Morgan Library and Museum in NYC and caught an exhibit by Nina Katchadourian, self-described artist of found things. Included in the collection was a series of book stacks, each arranged so that the titles, read from top to bottom or left to right, told a story. Inspired, he went back to his own book shelves to find the conversations hidden there.

Calling for Your Contribution to “Moment of Zen”

What is YOUR moment of Zen? Send me your photos, a video, a drawing, a song, a poem, or anything with a visual that moved you, thrilled you, calmed you. Or just cracked you up. This feature is wide open for your own personal interpretation.

Come on, go through your photos, your memories or just keep your eyes and ears to the ground and then share. Send your photos/links, etc. to me by replying to this email or simply by sending to: elizabethmarro@substack.com. The main guidelines are probably already obvious: don’t hurt anyone -- don’t send anything that violates the privacy of someone you love or even someone you hate, don’t send anything divisive, or aimed at disparaging others. Our Zen moments are to help us connect, to bond, to learn, to wonder, to share -- to escape the world for a little bit and return refreshed.

I can’t wait to see what you send!

And remember,If you like what you see or it resonates with you, please share Spark with a friend and take a minute to click the heart ❤️ below - it helps more folks to find us!

(Wherever possible the books here are linked to bookstore.org where every purchase helps local bookstores and, if they link to our own page, they generate a commission. )

Thanks for reading Spark! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

I couldn't pick a favorite poet, there are so many. Right now, for example, I can't get enough of the contemporary poet, Megan Fernandes. But I go back to Seamus Heavy, Sylvia Plath, T.S. Eliot, and Czeslaw Milosz, over and over again, for wisdom and for words.

Milosz, especially, writing poetry against a backdrop of war and the dissolution of civilized society, is always a solace, as with these stanzas from "One More Day":

And though the good is weak, beauty is very strong.

Nonbeing sprawls, everywhere it turns into ash whole expanses of being,

It masquerades in shapes and colors that imitate existence

And no one would know it, if they did not know that it was ugly.

And when people cease to believe that there is good and evil

Only beauty will call to them and save them

So that they will still know how to say: this is true and that is false.

Most all the things I've tried in my life (whether success or fail) were likely inspired by something I read. ha! Thank you for featuring Andrew Merton, such wise words. My favorite poem is Diagnosis by Sharon Olds. My favorite poets are Mary Oliver and Andrea Gibson, though I read many poets. I appreciate your including me and my work in this post. Thank you so much.