“The present changes the past. Looking back you do not find what you left behind.”

― Kiran Desai, “The Inheritance of Loss”

“People in this country, always worrying about how to eat, they pay someone good money to tell them: Eat this, don’t eat that. If you don’t know how to eat, what else can you know how to do in this world?”

― Imbolo Mbue, “Behold the Dreamers”

Home

The language is not yours. The terrain is strange, unfamiliar. The clothes, the customs, the pace, the food all remind you that this place is not your home.

Except that now it is.

When I encounter someone who has immigrated to America. I am meeting a person who has left her first home, possibly never to return, and to put down roots in soil that may be fertile, neutral, or unwelcoming. This journey is not for the faint of heart. I’m not sure I could do it. But then, I’ve never had to. The closest I’ve ever come is moving to California from the Northeast and that does not count, no matter what my friends back east may think.

And usually, a move like this is not about one person. It’s a move that alters the course for entire families. There are the people left behind. There are the children born here who are Americans from the moment of their births. They grow up differently than their parents, and differently from their friends who may be many generations away from the ancestors who landed here as strangers.

A few of my friends were born here of parents who immigrated here years ago. I used to sit in the kitchen of one of my friends while she chattered with her mother in Ukrainian. Impossible syllables raced off her tongue interrupted by English words like “okay” or “yeah” or the name of a television show. Then she’d get off the phone and we’d be back to talking about work, clothes, relationships, dreams, or the latest bits of gossip about famous people-- all in English that spilled out just as fast as the Ukrainian she’d just been speaking. She seemed to have two lives she was living at once.

In my old job, I was at lunch one day with my colleagues and realized that all three were born in another country. Two came here as children from Germany and Poland, the other later from India. All three were citizens. Every story at that table was different -- different impetus, different experience, different adjustment. Each, though, was the same in one respect: the journey.

I realize now there is so much I would like to ask them, but never have. I would like to learn how things looked to them when they were younger, how they look now, what their parents wanted for them, or what they wanted for themselves. I’m embarrassed that I’ve waited so long to be curious when I am normally a person who does not hesitate to ask questions. Part of me is worried that these questions might be too personal, but if I’m honest, it is also because I’m steeped in the assumption that “of course” others would rather be here, in America. I grew up with that assumption. Only relatively recently have I begun to question it more deeply and to realize that if I were to come to this country now, as an immigrant from another place, I’d see the high price we Americans exact from others who want to call this place home. My identity as an American would include another identity that I may or may not even know much about.

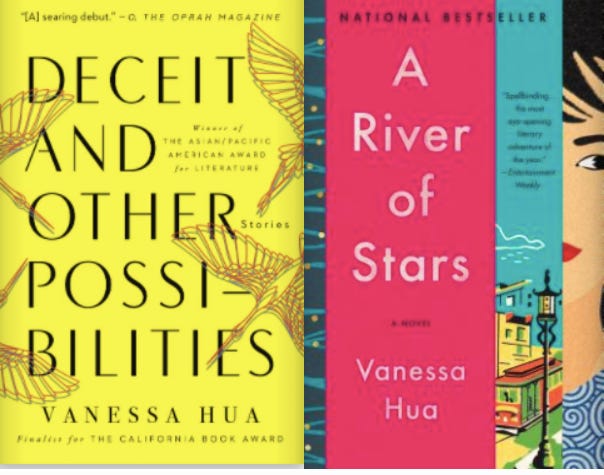

This is why the stories of writers like Vanessa Hua are becoming must-reads for me. Her first two books, a collection of short stories “Deceit and Other Possibilities,” and debut novel, “River of Stars,” takes us into the world of first-time immigrants and children of immigrants. A child of two Chinese immigrants, she grew up in a family where love was expressed not in words, but in actions and came with clear expectations.

“We had duties and responsibilities; theirs was to provide for the family, to pay for our clothes, our food, our home, our extracurricular activities, and other fees. The duty of the children was to excel academically, go to a good college and get a good job (and later on, get married and have grandchildren and take care of our parents when the time came). We understood these expectations without explanation. So much was left unsaid. Our collective burden, our inheritance. They’d abandoned everything familiar to make a life for their family here, so why look back, why bring up those struggles when you could look ahead? Yet I knew they cared for me every time they served me the most tender morsels—the plump prawn from their own bowl—or forced a sweater on me.” - Vanessa Hua, The Rumpus Interview December 2016.

In this interview from 2016, Hua goes on to explain that each of the ten stories in “Deceit and Other Possibilities,” explores what happens “in this environment of sacrifice and duty. My characters are squeezed by those expectations, and struggling with assimilation and cultural, language, and generational gaps.”

Her novel, “River of Stars,” concerns a different scenario altogether in which a mother comes to America so her child will be American but escapes her watchers so that she, too, can try to seek a life that is on her terms. In her interview below, Hua shares a few insights about writing and balance. This Rumpus interview, however, is a rich and thoughtful look at her compulsion to examine the immigrant experience in her writing and offers a look at all the ways this experience, though shared by millions, is unique to each individual.

Before we get to the interview, though, here are just a few more of the books and writers who have opened the window on this world for me and forced me to take a closer look at myself and the country I call home.

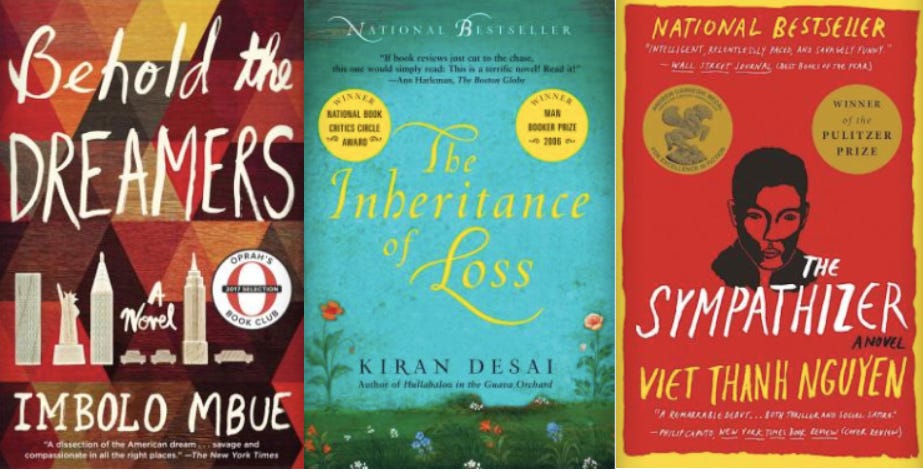

“Behold The Dreamers” by Imbolo Mbue tells the story of a Cameroonian immigrant whose fate becomes inextricably bound to a family undone by the collapse of Lehman Brothers in the mid-2000s. Mbue has a gift for humor, for detail, and for voice that makes you fall in love with her characters and keep turning the pages until you reach the surprising but satisfying end.

“The Sympathizer” by Viet Than Nguyen, this is a story of love, friendship, betrayal, war, and life after war. The novel earned the Pulitzer Prize for fiction for Nguyen whose parents fled Vietnam as refugees with him and his brother in the Seventies. They settled in northern California. I was absorbed by this book and equally absorbed by this interview with Nguyen that appeared in Consequence Magazine. You will see Nguyen interviewed in the excellent PBS series Asian Americans.

“Inheritance of Loss” by Kirin Desai. I read this book a long time ago. What remains with me today is a haunting sense of hope, and the trauma that comes with being found without anchor, without purchase in a new environment. It is not a novel about immigration so much as it incorporates the yearning that prompts an Indian father to send his son to America even as he continues to serve the orphaned niece of his boss. Desai switches back and forth between India and New York so that one feels a jarring juxtaposition; understands why the son conceals from his father in order to protect his father’s hope and pride. Home comes to mean something different for each character in the book. The novel won the Man Booker prize.

“Enrique’s Journey” by Sonia Nazario. This is the young-adult adaptation of Nazario’s nonfiction account of one boy who leaves Mexico to find his mother. A journalist by training, Nazario retraces the steps of the young man and along the way provides an insightful account of why young people risked their lives to ride the tops of trains (“la bestia)” to get to America.

A note from a child of immigrants on voting

When Irene, a Spark community member from Vermont, read last week’s post she wrote this short note that should inspire all of us:

“My parents were immigrants to this country. They escaped communism that took a hold of Eastern Europe. I remember how much they respected the privilege of voting as it was denied in their Motherland that they fled. They never missed an opportunity to cast their ballot. Although I don’t necessarily remember any discussions about the importance of voting, they passed on the importance of voting by example. I can’t imagine not exercising my right to vote.”- Irene, A Spark Community member from Vermont.

Have you protected your vote yet? Here’s some the information from last week’s post you, your loved ones, or your friends can use to get started right now: YOUR VOTE, YOUR VOICE. If you have a first-time voter in the family, there are some tips and resources that can help.

The Spark Interview: Vanessa Hua

This is what Vanessa looks like:

.

Here’s her Bio:

Vanessa Hua is a columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle and the author of A River of Stars and Deceit and Other Possibilities. A National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellow, she has also received a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, the Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature, and a Steinbeck Fellowship in Creative Writing, as well as awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Asian American Journalists Association, among others. She has filed stories from China, Burma, South Korea, Panama, and Ecuador, and her work appeared publications including the New York Times, Washington Post, and The Atlantic. A Bay Area native, she teaches at the Warren Wilson MFA Program for Writers, and elsewhere. You can find her here:

Twitter: @vanessa_hua and on IG: @mononoke97

FB: https://www.facebook.com/vanessahuawriter

Her books:

And here’s the interview:

Spark: What was it that compelled you to write the stories in “Deceit and Other Possibilities?”

VH: I usually start with a premise-- a what if that leads to a why? How did the character get themselves into a situation, and how will they find their way out of it.

Spark: What are the things that went undone in your life as you wrote them?

VH: You always have to give up something, don't you--time I would have spent with a partner, or my kids or self care, or on my community. Now that my twin sons are about to turn nine, I'm feeling nostalgic about the minutes, hours I stole away when they were young. On the other hand, with the pandemic, I'm spending more time with them than ever before. I cherish our daily walks and hikes, but a part of me is back to longing for time to myself. The juggle never ends!

Spark: How do you feel about this book compared to your debut, River of Stars, and others you --have written, published or unpublished? You've said that some of the stories were written years ago

VH: Deceit was originally published in 2016, after winning a contest at a small press. When the rights reverted back to me last year, I was thrilled that Counterpoint wanted to acquired and reissue it, with three new and previously stories. It's reached a new and broader audience, despite, even though it came out amid the pandemic. For that, I'm very grateful.

Spark: Have you written the book or story I sometimes think of as "the book of my heart"-- the one that you believe you must write no matter what -- or is that yet to come?

VH: I don't mean to be glib, but every book is "the book of my heart" -- just like every child of mine is my favorite. That said, I began my forthcoming novel during graduate school in 2007, and I'm about to send a revision off to my editor. Much has changed in the novel--which is about Chairman Mao's teenage lover--and much has changed in my life, but I needed those years to write the book I wanted.

Spark: As one of your followers since just before your debut, I imagine your life as packed to the brim with writing, teaching, family, and making sure that your books reach readers which you have done without sacrificing your gift for reflection and telling important, moving stories. Writer and activist Grace Paley once said "Life is too short, and art is too long." What do you think of when you read these words?

VH: Art is always calling, and the time we spend on it never feels like enough. But the time we have with our friends and family is just as vital, something that these past months have taught us all.

Spark: Have there been moments when life has seemed to be racing by for you or that you have questioned your decisions? How has this affected your life choices and what you choose to write about?

VH: Years ago, I wrote short stories whenever I could outside of my job as a daily journalist: before work, after work, on weekends, at lunch. While on a journalism fellowship in South Korea, I casually mentioned that I wanted to write a book. Another participant said, "Well, then write a book!" She was just making conversation, but it resonated with me. I had to make fiction the center of my life...or put another way, figure out how to put the best part of myself into my creative work. That's going to look different for different people--there's many different paths in the writing life. I ended up going to grad school, and in time became a freelance journalist as well as a novelist. It's a juggle, of course, and I have to make different decisions as circumstances vary. During Covid-19, I have to remind myself to be patient and gentle with myself, as patient and gentle as I would be any friend or student.

That’s it for this week. What have you been reading? Tell us so we can share it in our bookshop.org site. Every purchase through this page helps independent bookstores and, if we buy enough books, we’ll have some money to donate to a literacy program voted on by you all in this community. Thank you for reading. Thank you for being here.

Stay well. Stay Safe. VOTE!!!!

Betsy

And now…Your moment of Zen: Ring of Fire

Wonderful and I remember sitting with those co workers and thinking you came from New Hampshire...pretty foreign to me but not as you beautifully state in this piece not the same.