Welcome! You’ve reached Spark. Learn more here or just read on. If you received this from a friend, please join us by subscribing. It’s free! All you have to do is press the button below

In this issue:

What exactly is a bad mother? We know her when we see her

Bad mothers make for good reading: fiction recommendations and lists

Jane Austen’s meanest mom and real mothers trying to be good

But first…

Welcome to all new subscribers and thank you for joining us! We want to hear from you so let us know what you think, what you’re reading, what you’d like to talk about. If you’d like to catch up on past issues, here’s a link to the archives. And if anyone missed last week’s post about writing and reading while incarcerated, here’s the link: Stories Can’t Be Locked Up

And now…What is a Bad Mother?

Let’s face it, motherhood is one of those subjects that should come with a warning sign. I sat down to write what I thought would be a fun piece about the “bad mothers” in fiction and how they can, even from the relative safety of a typeset page in a made-up story, cause some of us to cringe, criticize, laugh, cry, then slam the book shut in fear or anger or both.

The problem started with trying to define “bad mother” which, of course, varies significantly according to who is doing the defining. A quick google search yielded an astonishing number of results that ranged from the very simple: “Good moms care, bad ones don’t” to the slightly more complex list involving neglect, putting one’s self or husband before the kids, not learning from mistakes, not perfect and feeling guilty or not perfect and forging ahead with hopes for the future, overindulging the kids, going against the mainstream of popular parenting practices, worried about what others think, and just plain “bad” people who happen to be mothers.

Then there was the problem of which path to follow. I lacked the time, discipline of mind, and literary chops to delve deeply into the dark themes that connect mothers who have come to us from the times of the mythical Medea to Elena Ferrante’s The Lost Daughter.

I was also lured by the ongoing discussion about the struggle for mothers to be recognized as worthy literary heroes: flawed, struggling, brilliant, human and not just supporting characters in a male world or leads in a category of fiction thought of as women’s fiction.

Then I remembered what got me going on this idea in the first place: the women who read my novel Casualties and took the time to tell me how much they hated Ruth, my protagonist, a single mother and executive with a defense contractor. One reader told me that Ruth was selfish, insensitive, and unrealistic. She went on to assert that a real mother would never have made the decisions Ruth made. Another wrote to tell me that women like Ruth did not deserve to have children. A third reader who met with me in a book club said very little as we talked about the book but she was clearly upset and when she was asked for her feedback, she shook her head angrily and passed.

She contacted me personally later on to explain and apologize; she felt she’d been rude but the discussion and the story had struck a nerve that had nothing to do with the book and everything to do with her own story. The apology was lovely of course but not necessary. She was only doing what we all do when a story reminds us of something real, something difficult or painful. We can’t help but bring our own stories to whatever we read.

This is why the definition of “bad mother” is so slippery. So much depends on who is reading the story. Mothers may silently measure the performance of a character against her own or vice versa. Readers who have never been and never will be mothers may be haunted by their mothers even if they’ve never met them. Still others have more than one mother figure in their lives which leads to all kinds of possible reactions to the mothers, stepmothers, grandmothers, aunts, adoptive mothers, and biological mothers they might find in a novel or short story.

I was warned by some readers of my early drafts that I was making working mothers look bad. Ruth allows her work to sweep her up at a critical moment between her and her son — she postpones a lunch meeting with her son to take care of a work emergency and nothing is the same ever again. Her decision is one that many - mothers and fathers, working or staying at home - face every day, often with crossed fingers.

I was struck by the urgency that accompanied this feedback. It was almost flattering that these readers thought my novel would reach enough of an audience for this to be a concern. But it also reflected their own stories, how hard they had worked - how hard we all had worked – to keep the balls up in the air, to be good parents, good mothers, and to succeed in our jobs and feel proud of our work — and how we felt failure nipping at our heels every minute of every day.

The truly frightening thing about Ruth and other mothers in fiction is not that they work, or are - god forbid - unlikeable women. The truly frightening part is how easy it is to slip up. There are a frightening number of ways for a mother to fail, to slip from that gray zone of “only human” to the unforgivable. With children in the picture, the stakes are huge. Which is one reason mothers are rich sources of material for a writer.

Think about the mothers in the last few books you’ve read. What was your reaction to them? Did you recognize her? Was she a monster, invisible, superlative? Would you like her for your mother?

Bad Mothers Make for Good Reading

Books:

Berthold Brecht’s Mother Courage in Mother Courage and Her Children makes a living off the thirty-year war that ultimately kills her children.

Nadia, the young, grieving protagonist in Britt Bennett’s The Mothers who falls for the pastors son, gets pregnant, and has a secret abortion paid for by the pastor’s wife. Like all secrets, this one has long-term reverberations.

Lilly, the mother of Roy Dillon in Jim Thompson’s noir novel The Grifters considered one of the best studies of con men around. In the movie version Angelica Huston plays Lilly and tells her son, “I brought you into this world, I can take you out.” She does.

Lists:

Jane Austen’s Meanest Mom

I asked Plain Jane over at the Austen Connection who she would pick as the worst mom in all of of Jane Austen’s novels. The winner: Mean Mrs. Ferrars from Sense and Sensibility. Read on to find out why from Plain Jane herself:

Mrs. Ferrars is the formidable mother of Sense and Sensibility heartthrob Edward Ferrars. Edward is played by Hugh Grant in Ang Lee’s wonderful 1995 film adaptation of the book, which also stars actor and screen-writer Emma Thompson.

Why we love to hate her:

Mrs. Ferrars does not appear until late in this book, but her awful presence pervades it. Because of her financial domination of both of her sons, the mild older brother Edward struggles to find his place in life. He’d like to be a clergyman, but we learn that his family, namely his mother, finds this too unimpressive. Because of a lack of familial support, he harbors a secret engagement that threatens to ruin his life and his love for our Austen heroine Elinor.

Ultimately, Mrs. Ferrars disinherits Edward because of his disastrous engagement and purely out of spite gives that inheritance to the flamboyant younger son, who turns around and flouts her trust by marrying the very woman Edward had been disinherited for being attached to!

All this leaves the way clear for Edward to marry Elinor, and they proceed to scrape together what financial and familial support they can.

But everything this couple achieves happens in spite of this awful mother, who is truly a force to be reckoned with.

Way to go, Edward and Elinor!

See more on Mrs. Ferrars and other bad moms from Austen at this week’s edition of the Austen Connection. And to see a fantastic talk on the power of Mrs. Ferrars and what Austen is doing with this character, check out Oxford University's Dr. Octavia Cox’s YouTube lecture on Mrs. Ferrars, money and inheritance.

Real Moms, Trying to Be Good

“People often say that childbirth is perfectly natural; that our bodies were designed to do this. But you can say the same about death.” - Cindy DiTiberio, We Want Care, Not Cards

Cindy DiTiberio is an editor, a ghost writer, the publisher of Literary Mama and the voice behind The Mother Lode newsletter in which she explores how to mother young children in these times without losing her identity, her strength, herself. I don’t envy where she is in her life. I read her newsletter from the safer shores of post-motherhood. I read The Mother Lode to understand what has changed and what has not changed for women who are raising children in today’s world while working, nurturing relationships, trying to have a few hopes and dreams or just a moment to breathe or read a book. Every now and then, she writes about what she has been reading:

Animals That Make Any Mother Feel Great By Comparison

File this under random findings while researching for this newsletter.

Turns out that some of the cutest animals are some of the worst mothers. Pandas are noted for their negligence and will abandon the weakest of two twins. Harp seals dote on their pups for twelve whole days and then abandon them to mate again. Cuckoos lay their eggs in others’ nests and continue their lives as single birds. Here are The 9 Worst Moms in the Animal Kingdom.

That’s it for this week, except for one thing. I don’t want to forget to wish the mothers among you a happy day tomorrow. May you celebrate in whatever way works for you. At the same time, I again invite us all to consider how the holiday may be difficult for many. I’m linking back to last year’s post which has some links for how to navigate the day for ourselves and to make it a bit easier for someone you know.

Ciao for now.

Gratefully,

Betsy

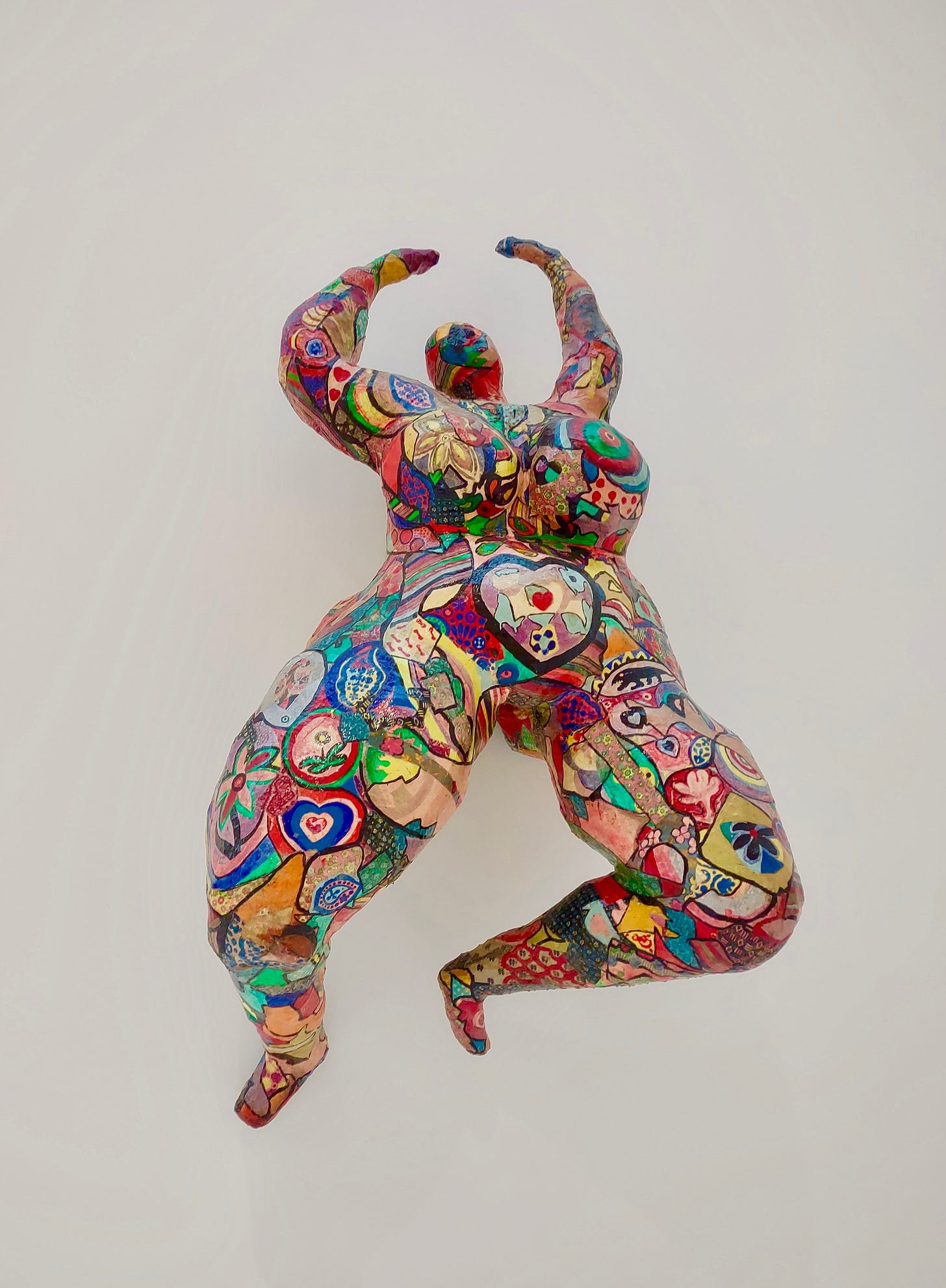

P.S. And now, your moment of Zen…Niki de Saint Phalle

There she was, one of the Nanas, on the walls of the La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art, big, beautiful and radiant with color.

Calling for Your Contribution to “Moment of Zen”

What is YOUR moment of Zen? Send me your photos, a video, a drawing, a song, a poem, or anything with a visual that moved you, thrilled you, calmed you. Or just cracked you up. This feature is wide open for your own personal interpretation.

Come on, go through your photos, your memories or just keep your eyes and ears to the ground and then share. Send your photos/links, etc. to me by replying to this email or simply by sending to: elizabethmarro@substack.com. The main guidelines are probably already obvious: don’t hurt anyone -- don’t send anything that violates the privacy of someone you love or even someone you hate, don’t send anything divisive, or aimed at disparaging others. Our Zen moments are to help us connect, to bond, to learn, to wonder, to share -- to escape the world for a little bit and return refreshed.

I can’t wait to see what you send!

Enjoy your Mother's Day celebration, Betsy! I recently finished The Giver of Stars and marveled at the multi-dimensional character, Margery. She was determined to be independent and almost manlike, the core of her success as a WPA librarian on horseback in Appalachia. Unanticipated motherhood altered her life significantly.

The most haunting book on motherhood I ever read was Sophie's Choice...

Happy Mothers Day, Betsy. I'm almost done with East of Eden. I'm glad Cathy Ames was included on one of the lists. A mother who works in the world's oldest professions after abandoning her husband and children days after the birth.